The early years

The realisation that unregulated development could destroy the countryside that represented the England that so many had fought for in the trenches of the First World War triggered a series of appeals to government to take control of the sprawling building boom of the mid-twenties. The result was the first incarnation of CPRE, the countryside charity, as the Council for the Preservation of Rural England.

1925

Patrick Abercrombie, president of the Town Planning Institute, urged housing minister Neville Chamberlain to regulate ‘residential growth [by] the ribbon unrolled along the roadside … the new method which is unconsciously being adopted through the whole of England as a result of the new motor-omnibus services and use of private motor-cars. Soon this green and pleasant land will only be glimpsed through an almost continuous hedge of bungalows and houses!’

Abercrombie argued that not only would ribbon development ‘inflict maximum destruction on rural beauty’, but it also represented ‘the most extravagant method [of housing] to sewer, water, light and police’.

Guy Dawber, president of the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA), wrote an impassioned letter to The Times pleading for ‘immediate steps to be taken to prevent the whole countryside being littered with architectural eyesores. On all sides we hear protests made, but nothing is being done to stop it. Every man is a law to himself and builds as he wishes with a selfish disregard of his neighbour.’

1926

Guy Dawber wrote to 15 organisations with an interest in the future of the countryside. ‘The time has come when definite steps should be taken to prevent the further destruction and disfigurement of Rural England. The problem is a two-fold one: the conservation of what is beautiful and interesting in our countryside and towns and villages; and the encouragement of the right type of development.’

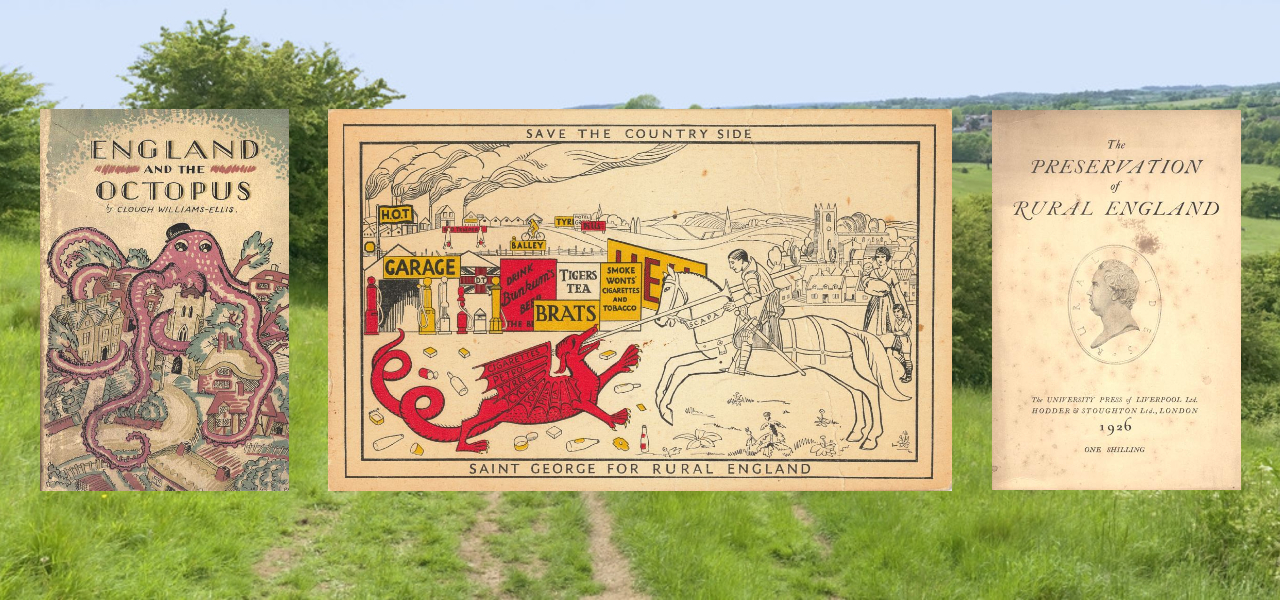

Pioneering planner Sir Patrick Abercrombie published The Preservation of Rural England, calling for a national joint committee to preserve the countryside. This was one of the five key publications of the year, according to the British Library’s Chronology of Modern Britain. Abercrombie believed a ‘National League for the Preservation of Rural England’ could unite ‘the existing specialised societies’ and ‘focus attention upon the destruction of the beauty of the English Countryside which is not only robbing the country of one of its most precious assets but is uneconomic’.

‘There is no time to be lost if the English countryside is not to be reduced to the same state of dreary productiveness to which the English town sank during the industrial revolution of last century. If we have allowed Adam Smith’s doctrine of the ‘invisible hand’, gradually creating order out of individual success, to dominate our industrial towns and coalfields, we cannot afford to wait for a similar emergence of economic beauty from a devastated countryside. It is poor economics to bring prosperity and improvement in one direction and at the same time induce deterioration.’

Calling for the regulation of building across the whole country, Abercrombie wrote: ‘It is high time to drop the clumsy word “town-planning” as applied to the country. The term therefore proposed was ‘Rural Planning”.’

His manifesto was subtitled ‘The control of development by means of Rural Planning’. It proposed the basis for the ‘town and country planning’ system which has done so much to save what he called ‘the normal English countryside’. Abercrombie’s manifesto also suggested ‘a bold and wide policy should be pursued towards the creation of a series of national parks for the preservation of “wild country” with universal appeal for civilised man’

Pointing out that the ‘wildest country’ often had the largest mineral deposits, he argued that ‘public ownership will have to step in before the business exploiter gets thoroughly to work’. He also provided the basis for CPRE’s campaign for green belts, proposing that local authorities ‘reserve land for agricultural zones or farming belts’ to prevent towns and cities coalescing and keep fresh produce close to urban markets.

CPRE formed on 7 December 1926 as the Council for the Preservation of Rural England, with Abercrombie its honorary secretary. Dawber, as chairman, introduced the meeting by ‘inaugurating a movement which, we hope, will result in the preservation of rural England, the saving of that CPRE national treasure of beauty which means so much to all of us, and which we see threatened with imminent destruction’. Dawber felt the new council – which included the National Trust, Women’s Institutes, Commons Preservation Society and SCAPA – represented a coalition the like of which had ‘never before been brought together for a great common purpose’.

Health minister Neville Chamberlain addressed the meeting to welcome the formation of ‘a body of authoritative character’ which could ‘draw attention to threats against specific beauty spots’ and ‘offer local authorities technical advice and assistance’. Chamberlain’s speech highlighted the ‘spoiling of undefiled countryside by ribbon development’ as the biggest ‘aesthetic abomination’ facing rural England. ‘Besides being undignified, if not positively offensive, it is also uneconomical, wasteful and inconvenient’.

1927

Influenced by Abercrombie’s CPRE manifesto, health minister Neville Chamberlain asked the Greater London Regional Planning Committee to consider providing London with ‘an agricultural belt’.

Violet Christy gave one of the earliest speeches championing CPRE in April 1927. This was to the Pioneer Club – an institution founded by the suffragist Emily Masingberd to engage women in progressive politics and social campaigning. Violet went on to give dozens of illustrated talks around the country on the work of CPRE before becoming a lecturer.

1928

CPRE Architectural Advisory Panels were set up with the Royal Institute of British Architects to advise local authorities and developers on good quality design for new buildings.

Clough Williams-Ellis published the CPRE-commissioned book ‘England and the Octopus’, which helped make urban sprawl a national issue. The book was a major influence on writers including George Orwell, Evelyn Waugh and DH Lawrence.

CPRE campaigning led to the Petroleum (Consolidation) Act of 1928. This enabled local authorities to enforce the removal of advertising on and around roadside garages, often located in sensitive tourist destinations and picturesque villages.

CPRE’s Save the Countryside travelling exhibition began its journey around the country, contrasting examples of ‘bad development’ with positive solutions. Westminster Hall was one of over a hundred venues visited by the exhibition between 1928 and 1930. MPs praised it for highlighting the ‘lack of forethought in the development of the countryside’.

1929

During the general election, the leaders of the three political parties (Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin, Ramsay MacDonald and David Lloyd George) wrote a joint letter to The Times, endorsing the work of the CPRE and its appeal for funds. After MacDonald was elected, CPRE wasted no time in sending a memorandum to the prime minister urging the case for national parks. In response, the government set up the Addison Committee on National Parks.

CPRE used its national conference in Manchester in November 1929 to instigate ‘National Reserve Committees’ in potential national park areas. The Lake District National Reserve Committee was formed that weekend under the guidance of Abercrombie and John Dower. The committee later became the Friends of the Lake District in 1934, going on to represent CPRE in Cumbria.

In December, Abercrombie and the geographer Vaughan Cornish gave CPRE’s evidence to the Addison Committee. Both stressed the importance of national parks for the recreation of those living in cities. Abercrombie listed 12 distinct areas that might be most suitable for national park status, saying: ‘Of the 12 areas given in the list, the High Peak and the South Downs would appear to have the first claim from the population point of view; from the point of view of national interest and intrinsic beauty the Lakes and Snowdonia, Exmoor and Dartmoor.’

1930

In line with CPRE’s evidence, the Addison Committee report recommended the creation of national parks ‘to safeguard areas of exceptional natural interest against disorderly development and speculation’ and ‘to improve the means of access for pedestrians to areas of natural beauty’.

CPRE drafted Sir Edward Hilton-Young’s Rural Amenities Bill, leading to a reference to the preservation of rural amenities in the King’s Speech to Parliament. This was the first acknowledgement of the need for legislation to protect the countryside.

CPRE won support from the Women’s Institutes for its suggestion that rural councils must enforce anti-litter bylaws and provide waste collections to cut down on dumping in hedgerows and ponds. CPRE and the WIs began joining forces in setting up local ‘Anti-Litter Leagues’ to organise litter picks and educate children on the litter problem.

CPRE’s national conference on the Use and Enjoyment of the Countryside included a speech from historian GM Trevelyan. He encouraged ‘our town population and young people, to go out into the country and use it properly in the way of walking and camping’.

1931

The Minister of Transport appointed CPRE as official advisers to the Electricity Commissioners on the positioning of overhead electricity cables to minimise visual impact on the countryside. 40 cases were dealt with in 1931, and many more in the years to come.

1932

The Town and Country Planning Act 1932 successfully embodied the recommendations of CPRE’s Rural Amenities Bill. It was the first legislation to accept the desirability of universal rural planning. Consequently, state loans for the preservation of public open spaces tripled to almost £2.5 million between 1932 and 1936. The amount of England and Wales covered by planning schemes increased from 7 million to almost 20 million acres during the same period.

CPRE Sheffield and Peak’s Ethel Haythornthwaite’s skilful negotiation helped acquire 448 acres of threatened land at Blacka Moor, which would soon become part of a Sheffield green belt.

CPRE attended many local inquiries advocating the importance of preserving common open spaces. This helped to ensure the Rights of Way Act 1932 contained powers to make established paths across private land ‘public rights of way’. That year, CPRE commissioned a detailed report on Access to the Moorlands in the Peak District by Phil Barnes, a renowned climber and photographer. Barnes argued the re-opening of ‘trespass routes’ like Kinder Scout would actually reduce damage to moorland habitats and help encourage the growth of the youth hostel movement.

1933

Raymond Unwin’s proposed Green Girdle for London – which was to become Britain’s first green belt – was endorsed by CPRE. We had proposed an ‘open belt’ of protected countryside around London three years earlier.

CPRE gave evidence to the Select Committee on Sky-Writing to call for the protection of the sky as a national asset.

1935

The Restriction of Ribbon Development Act 1935 crowned CPRE’s nine-year campaign against sprawl. Highway authorities were now able to control building within 220 feet of roadsides. They could also acquire land up to 220 yards from a highway to prevent ‘the erection of buildings detrimental to the view from the road’.

CPRE introduced a national scheme of countryside wardens to educate the public on responsible behaviour in the countryside and enforce a ‘Code of Courtesy for the Countryside’ devised in partnership with the Scouts and Guides Associations. This was later adopted by the National Parks Commission as the ‘Country Code’. By July 1935, 276 Wardens were enrolled across the country.

CPRE and the Campaign for the Protection of Rural Wales set up the Standing Committee on National Parks to represent all interests concerned in securing the designation of national parks. It is now an important organisation in its own right, known as the Campaign for National Parks.

1936

CPRE and the Forestry Commission signed a joint agreement to prevent large-scale commercial forestry plantation in the Lake District’s central fells. CPRE’s negotiations had been greatly assisted by the Friends of the Lake District’s ‘red line’ maps, drawn up by John Dower and later used as the basis of the national park boundary.

The Times’ editorial celebrating CPRE’s tenth anniversary in December 1936 noted that, as well as spreading ‘knowledge of beauty, pride in beauty, and the will to preserve beauty’, CPRE had created a growing understanding ‘that the beauty of rural England has a commercial value: Americans and other foreigners come to see it and are upset when they find it spoiled. To scoff at “amenity” is now both old-fashioned and bad business.’

CPRE’s influential report, The English Coast: Its Development and Preservation, recommended ‘the reservation all around the coast of a belt of open space, free from building’ on the principle that ‘it should be available in perpetuity for the benefit of the public’.

1937

On behalf of CPRE and the National Trust, Clough Williams-Ellis edited Britain and the Beast. This was a collection of pieces from leading public figures making the case for state intervention in landscape conservation.

1938

CPRE produced a film as part of its campaign for national parks. Rural England: the Case for the Defence was shown in 925 cinemas across the country. It received good reviews from The Sunday Times and the BBC, and represented England at the 1939 World’s Fair in New York.

The Metropolitan Green Belt Act was passed, stopping London’s sprawl in its tracks. This came months after Patrick Abercrombie warned at a national CPRE green belt conference that without one, London would ‘grow continuously in all directions’.

Despite the rush to build aerodromes and munitions factories in the run up to the Second World War, Neville Chamberlain’s government had the foresight to appoint Patrick Abercrombie as a consultant in the process of locating them. This ensured that ‘other national interests, especially our finest unspoilt scenery, shall receive due consideration before sites are selected’.

1940

National Gallery director Kenneth Clark initiated the Recording Britain scheme for underemployed artists to produce watercolours of ‘places and buildings of characteristic national interest exposed to the danger of destruction by the operations of war’.

Upon hearing of the scheme, London Underground supremo Frank Pick suggested that the painter Charles Knight should capture for posterity the beauty of the South Downs, then at risk from imminent invasion by British builders. Pick had been working with CPRE throughout 1939 in the successful campaign to protect 700 acres of the South Downs around Ditchling from a ‘garden city’ of 10,000 inhabitants.

After commissioning Knight, Pick enlisted CPRE’s help in suggesting other locations for a ‘Record of Disappearing Britain’. When 16 of CPRE’s county branches suggested landscapes as threatened by irresponsible construction as Nazi bombs, Clark was forced to direct his painters to prioritise ‘fine tracts of landscape which are likely to be spoiled by building developments’.