Life on the river

Spring is in the air, and with it, an abundance of new life. Here, some of CPRE’s favourite nature champions reveal the springtime wildlife sightings that always lift their spirits on a waterside stroll.

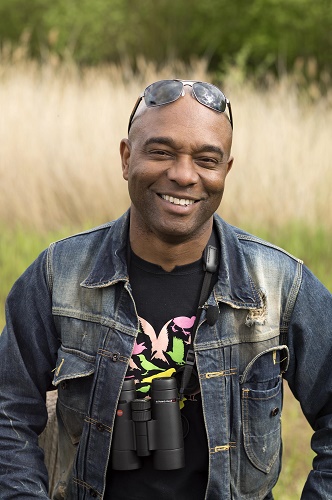

David Lindo on mallards

The mallard is a ubiquitous denizen of almost every waterway in the UK. From hanging out on temporary puddles in brownfield sites to riding the waves of a rough sea, it is up there with the pigeon and sparrow as one of the world’s most recognised birds.

The male, or drake, is adorned with a bottle-green head and mauve chest whilst the female, or duck, is the classic nondescript streaky brown. It is her alone that utters the familiar ‘quack’ that we all know and love. Despite their apparent ordinariness, they are fascinating creatures to observe. Their prenuptials can be quite violent and sometimes involve several males pursuing a solitary female.

Mallards are renowned for nesting in crazy places, most notably on the balconies of high-rise apartment blocks, sometimes miles from the nearest lick of water. So think again when you see mallards swimming serenely in your local park!

David Lindo, aka the Urban Birder, is a wildlife presenter, educator and writer whose latest book is How to be an urban birder (Princeton/Wildguides).

Amy-Jane Beer on mayflies

The UK’s 50 species of mayfly spend the majority of their lives as aquatic larvae known as nymphs, and emerge in spring or summer as short-lived flying forms, whose sole purpose is reproduction. Watching from water level, you can see individual insects struggle free of the surface tension and rise like tiny angels – an exquisite sight.

Not all mayflies appear in May, but within a given species and area, emergence tends to be closely coordinated. This increases their chances of finding a mate and gives a measure of safety in numbers, as they are weak fliers and targeted by all manner of predators.

In 2017 we were drawn to our local river, the Yorkshire Derwent, by an astonishing feeding frenzy, in which a column of birds hundreds of metres high was stacked by species – flycatchers and wagtails feeding close to the water, above them martins and swallows, then swifts, and finally a vast flock of gulls – all gorging on a bumper hatching of mayflies. Unforgettable!

Dr Amy-Jane Beer is a biologist, nature writer and author, whose next book The Flow (Bloomsbury) – all about rivers – is due out in 2022.

Tom Moorhouse on great crested grebes

Great crested grebe: the words encapsulate the bird. There’s a crispness in the ‘crested’ that catches their staccato movements and no-nonsense stares. The ‘grebe’ suggests an almost comic cuddliness, but the ‘great’ forces you to step back and admire their ‘don’t mess with me’ attitude. They are elegant and quick, exotic and familiar – just uncommon enough to be a rare treat.

Spotting these guys is simple if they’re around – you need no equipment (but binoculars can help) and they will happily perform in the open water as you watch from the bank. You can find them all year round, but the low reeds in spring present a great opportunity for an unobscured view of their elaborate courtship dances. Head out to a lowland river, lake or canal, and you might just get lucky…

Dr Tom Moorhouse is an ecologist and author whose latest book, Elegy for a River: Whiskers, claws and conservation’s last, wild hope (Double Day) is out now.

Megan McCubbin on grass snakes

A shy and timid creature basks in the sunshine amongst the tall aquatic vegetation that lines the sides of the river. With most of its long body submerged under the surface and its eyes peeking above, you’ll be incredibly lucky to catch a glimpse.

This wonderful reptile is, of course, the grass snake. After emerging from hibernation in between March and April, they’re a true sign of spring, and can easily be identified by their grey colouration and yellow and black banding around the neck.

A grass snake is an indicator of a healthy river system. To see one is always exciting, but to me it means so much more because I know that ecosystem is thriving. We have to enjoy and protect our freshwater environments; they are vital. And to me, the grass snake embodies that.

Zoologist Megan McCubbin is a Springwatch presenter and co-author of Back to Nature: How to love life – and save it (Two Roads) with Chris Packham.

Derek Gow on beavers

My favourite waterside creature is, of course, the beaver. Beavers are the most amazing engineers, whose construction activities offer living space and life opportunities to a whole host of other creatures.

Their field signs are relatively easy to observe: felled trees with distinctive chiselled tooth marks in their ‘pencil sharpened’ stumps; gigantic stick-nest lodges cemented with mud and the root systems of aquatic plants; and of course, their dam systems, of all sorts of shapes and ingenious designs.

Beavers are being reintroduced to Britain after an absence of perhaps 200 years. It’s been great to play a role in returning these wonderful creatures to their natural space.

Farmer-turned-ecologist Derek Gow charts his quest to restore beavers to British waters in Bringing Back the Beaver (Chelsea Green, £20).

Mya-Rose Craig on kingfishers

I live in a small village in the Chew Valley, south of Bristol, and we’re lucky enough to have a pond. Each day during lockdown, I have walked past and it has been there, sitting in a tree above the water: the kingfisher that brings so much joy to my day.

I love kingfishers for their beautiful bright colours, their ability to dive for fish, and their personalities. The best places to see these iconic birds are near ponds, streams, rivers and lakes which have branches that overhang the water.

These are where kingfishers will perch, waiting to attack. If you are lucky enough to spot one on a branch, you’ll see its bright blue feathers with an orange front; but it may be that you only see an exciting flash of blue as it takes its plunge.

Dr Mya-Rose Craig is a birder, founder of the Black2Nature charity, and blogger (@BirdgirlUK).

Jack Perks on pike

Pike are a bit like freshwater sharks – they have this reputation as toothy, cold-blooded predators. Put it this way: if you were to put a load of pike in a tank, you’d eventually end up with just one, very fat, pike. It’s a dangerous business being a male pike, because females are much bigger, and if they don’t like the look of potential suitors, they might just eat them.

You get some pretty big pike – the British record is 46lb, and they can easily reach around three foot, maybe even four. It’s always a thrill to be in the water with them. As predators, they take a lot of fish, but also frogs, water voles, and even ducklings.

But there’s a softer side to them, too, which comes out during the breeding season from February to March (or into April in bigger waterways). Males will gather around a female and one will eventually fight off the rest and escort her down to the weeds to breed. He’ll vibrate along her flanks, and she’ll release her eggs for him to fertilise. It’s quite a tender – if daring! – romance.

Pike are found in rivers and lakes all over the country, and as they come into the shallows to breed and spawn in springtime, so they’re a relatively easy fish to spot. If it’s sunny, they’ll come to the surface and sun themselves a bit, or if it’s a big pike, you might notice them splashing around. You might confuse them with a log at first – but once you’ve spotted that slender shape, there’s nothing else quite like it.

‘Naturalist with a camera’ Jack Perks regularly films wildlife for the likes of Countryfile and Springwatch.

A version of this article was originally published in CPRE’s award-winning magazine, Countryside Voices. You’ll have Countryside Voices sent to your door three times a year, as well as access to other benefits including discounts on attraction visits and countryside kit from major high street stores when you join as a CPRE member. Join us now.