An introduction to the English planning system

An introduction and informative background to the English planning system and application process. It aims to arm you with the expert knowledge you need to effectively participate in the democratic planning process. This is the shorter web version of our planning guide and should answer most or all of your questions, however you can also click here for the full and comprehensive guide.

Why is planning important?

The planning system exists to ensure that places are developed or protected in the public interest, providing checks and balances on the private sector and ensuring that necessary infrastructure and public services are delivered where they are needed.

An appropriate balance must be struck between delivering new developments such as new schools, homes and offices, and protecting places and buildings that are important to all of us. Planners help create well-designed places while safeguarding National Parks, World Heritage Sites, and Listed Buildings for the future.

The planning system aims to ensure that all views on new development are considered. The public can view and comment on planning applications to help shape decisions. By responding to applications, you can push for choices that benefit your local area.

England’s planning system is discretionary. Every application is judged on site-specific circumstances, with policies interpreted accordingly.

When is planning permission needed?

Development in England requires planning permission. The type of permission required will depend on the development proposed. In general, developments will fall under three categories: householder application, major development and minor development.

Householder application

Involves the development of an existing dwelling house (residential property) or development within the curtilage of a dwelling house.

Major development

Includes mineral extraction; waste; housing with >10 dwellings or covering more than 0.5 ha; developments of floorspace or sites of over 1,000m2; site development of >1ha; land use change >1,000 m2.

Minor development

Any application that doesn't fall in the major development criteria, such as a residential development with less than 10 dwellings or a change of land use of less than 1,000m2.

There are also separate permissions for Listed Buildings and outdoor advertisements. These are dealt with later in the guide.

It is always best to contact your local planning authority hereafter the LPA if you are unsure if planning permission is required and what type of development has been proposed. They will be able to provide advice and act if necessary. In most districts and urban areas, the LPA will be a part of your local council. In National Parks, however, the LPA will be the Park Authority.

Other types of planning permission

This guide is designed to help you respond to planning applications for development proposals. However, some projects may need extra or separate consents outside the planning system.

Special planning rules apply in protected areas, such as National Parks, the Broads, National Landscapes, and conservation areas. They also apply to wildlife sites like Special Areas of Conservation, Special Protection Areas, Ramsar sites, National Nature Reserves, Sites of Special Scientific Interest, and Green Belts.

Some of these special cases, and where additional consents may be needed, are set out in detail below.

How is planning permission granted?

Permitted Development

Some developments have permitted development rights, but the planning authority must approve the proposal’s details before work begins. In these cases, the authority can request changes to a development’s location or appearance but cannot challenge whether the development should happen.

This applies to various developments, including:

- Outbuildings for farming and forestry

- Small-scale solar PV panels

- Telecommunications masts under 15 metres

- Converting farm buildings or offices into homes

Under the Town and Country Planning (General Permitted Development) Order 1995, local authorities can install structures like bus shelters or kiosks without full planning permission. They also decide on their own applications, for projects they carry out or on land they release for others to develop.

County councils can grant themselves planning permission for major projects like roads and schools. They also handle all planning applications related to minerals and waste, deemed ‘county matters’.

Planning applications to the local authority

For most planning applications, applicants submit development plans to the local planning authority. If you live in a two-tier local authority system—consisting of a county and district council—your district or borough council usually makes planning decisions. However, in areas with a unitary authority, it acts as the local planning authority.

In rare cases, the local authority must inform the Secretary of State before approving certain developments. This applies to proposals on Green Belt land, outside town centres, on playing fields, in World Heritage sites, or flood zones. If notified, the Secretary of State may ‘call in’ the application and decide the outcome after a public inquiry. This removes the decision from the local authority.

Development Consent Orders or DCOs

Applicants submit Nationally Significant Infrastructure Projects (NSIPs) or Development Consent Orders (DCOs) to the Planning Inspectorate (PINS). PINS manages the examination and consultation process for NSIPs. They review the evidence and recommend approval or refusal. However, the relevant Secretary of State makes the final decision on whether to grant a DCO.

Different types of planning applications

Full or Detailed Planning Permission

If granted permission, the applicant can proceed with the development, subject to any imposed conditions and legal agreement.

Outline Planning Permission

This application sets out the general principles for the development of a site or area. It is granted with conditions requiring the submission of a further detailed application.

Section 96A Amendment Application (S96A)

Can be used to amend an existing planning consent as long as the changes are deemed non-material. Whether they constitute non-material changes is up to the local planning authority to decide.

Section 73 Application or Variation of Condition Application (S73)

Seeks to vary an existing planning consent by amending a planning condition attached to the permission. This type of application effectively replaces the previous planning consent.

Submission of Detail for Planning Condition(s) Application

Most major applications will be approved subject to planning conditions. Submission of detailed applications effectively agree or ‘discharge’ planning conditions, to implement the full permission.

Hybrid Application

A hybrid application consists of a part detailed and part outline application. They are usually pursued for major, multi-phased developments where some of the detail is not known at application stage

Development Consent Orders (DCO)

DCO applications are only for Nationally Significant Infrastructure Projects (NSIPs) and are submitted to and examined by the Planning Inspectorate.

How are planning applications decided?

The development plan

Planning law requires that planning applications must follow the development plan unless other material considerations suggest otherwise.

The development plan usually includes a Local Plan with agreed planning policies for the area. At neighbourhood level, a finalised or ‘made’ Neighbourhood Plan also forms part of the development plan. Development plans contain general policies, strategic aims, thematic policies, and site-specific policies with explanatory text. A delivery and performance framework explains how the plan will be monitored. Online maps show allocated sites and designations like Green Belt, ecological zones, and Conservation Areas. You can inspect hard copies at your local authority’s planning office.

Start by checking the Local Plan Policies Map to see if the site has special designations. These may include Listed Buildings, Nature Conservation Areas, or Tree Preservation Orders. You can find the policies map online or ask the local planning authority for a printed copy.

If there are designations, you should refer to relevant local planning policy included in the adopted Development Plan.

Material Considerations

Material considerations are specific ‘planning issues’ that help case officers or committees decide on a planning application.

Case law gives local authorities flexibility to decide which considerations matter and how much weight to give them. Common material considerations include national planning policies, supplementary guidance, and technical issues at the site. Some developments need an Environmental Impact Assessment, which usually carries significant weight.

Other Material Considerations

Even if the site has no designations, relevant material considerations may help you decide whether to respond to the application.

There’s no legal definition of a material consideration, but examples include planning history, noise, density, height, flood risk, and national policy. You can find a longer list of material considerations in the full guide.

In England, there’s no legal right to a view. You can’t object to a development just because it blocks or obscures a view. Other issues that aren’t material considerations include construction disruption, property value loss, and matters covered by Building Regulations.

The person determining the application will decide whether something constitutes as material consideration.

National Planning Policies

National planning policies—such as the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF), Planning Practice Guidance (PPG), and National Policy Statements (NPSs)—are material considerations but not part of the Development Plan. NSIP applications should usually follow the relevant NPS. In future, governments may use new legal powers to create national development management policies (NDMPs). These policies are expected to cover Green Belt, heritage protection, and housing types in large developments. If introduced, NDMPs will override conflicting development plan policies.

Supplementary planning documents (SPD)

Supplementary Planning Documents (SPDs), sometimes called supplementary planning guidance (SPGs), add context and detail to development plan policies. They may include design guides, neighbourhood-specific advice, or affordable housing policies.

SPDs are not part of the development plan and carry less weight in planning decisions. However, they can still be a material consideration. Public consultation must take place before new guidance can influence planning application decisions.

Environmental Impact Assessment or EIA Development

Development with likely significant environmental impact may require an Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA). Some types need assessment automatically; others may qualify based on potential effects. Applicants first undergo screening to determine this. They submit a screening request to the local authority, which issues a decision—called a ‘screening opinion’—after a three-week period.

If the screening opinion confirms likely significant effects, an Environmental Statement must accompany the planning application. This statement explains how the development minimises harm and outlines any remaining impact. It should also explore alternative proposals. Once submitted, the public can review and comment on the statement.

Further information can be found here.

Who makes the decision?

Planning permission is granted either by delegated powers or by a Planning Committee. Under delegated powers, a case officer at the local authority makes the decision. Planning Committees consist of locally elected Councillors. Householder and minor applications are usually decided by case officers. Major or controversial applications are assessed in a report, with recommendations made to the Planning Committee.

Sometimes, the Mayor of London (for Greater London) or the Secretary of State (anywhere in the country) may ‘call in’ applications. They use special powers to make the final decision themselves.

Finding out about planning applications in my area

Local planning authorities must keep a public register of all planning applications, which should be easy to access.

A hard copy of planning applications, along with any maps, plans and supporting documents, is usually kept at the local planning authority’s central office. All applications, plans and supporting documents must also be available online.

If you struggle to find the application you are looking for, contact your local planning department’s duty officer. The preferred method of contact is likely to be via email, details of which you will be able to find on the application page.

The planning application process

Pre-application Consultation

Applicants proposing major developments are encouraged to consult local people before submitting a formal planning application. This helps identify local issues and shows how the development could address them. Early engagement can also reduce objections, as residents can comment beforehand.

Consultation before submitting an application isn’t legally required. However, some local planning authorities ask for a Statement of Community Involvement, explaining how the applicant engaged with the community. For Nationally Significant Infrastructure Projects (NSIPs), pre-application consultation with the local community is mandatory.

Meaningful engagement often leads to changes in the proposal before formal submission. It can resolve early concerns or highlight new ones.

Applicants usually hold events at local community centres, inviting residents to speak with the team, including architects and consultants. They often provide a website or email address for public feedback on the emerging scheme.

For further information on the pre-application process please refer to the Government’s Planning Practice Guide.

Post application submission

Validation

All planning applications must meet the Government and Council’s information requirements, known as validation requirements. Applicants must include all necessary details when applying. If anything is missing, the application cannot be validated.

National validation requirements are set in the Government’s Planning Practice Guidance.

Statutory Consultation Period

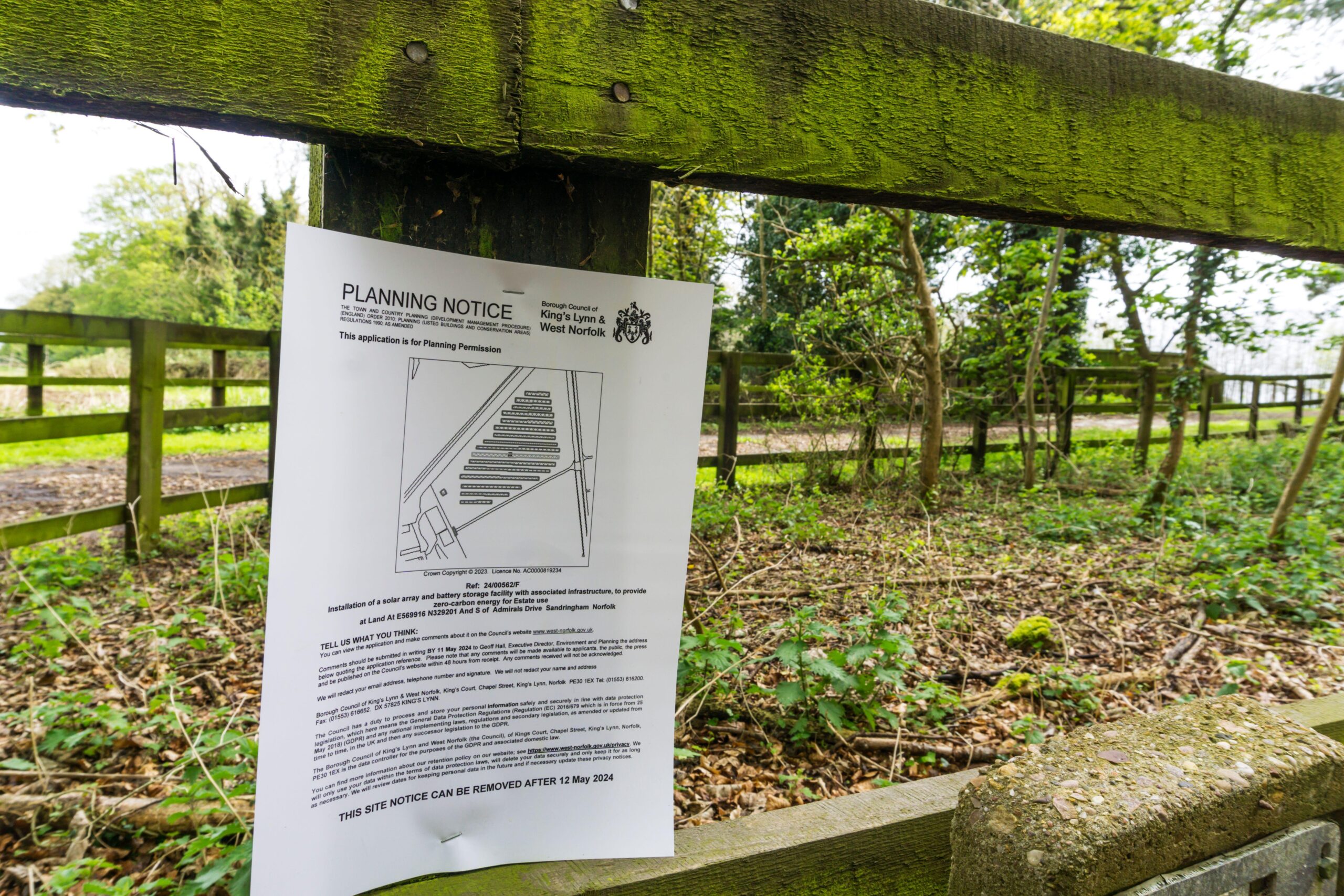

Local planning authorities must publicise new validated applications by displaying a ‘site notice’ for at least 21 days. This ensures neighbours and interested parties are aware of the proposal. The notice must be clearly visible on or near the site.

Local planning authorities also consult various stakeholders known as Statutory Consultees. The full list is available in the Government’s Planning Practice Guidance.

The public has 21 days to review and comment on an application. This statutory consultation period starts from the date the site notice is posted or published, not the application submission date. Sometimes the consultation period is extended, especially if neighbours weren’t properly notified or if it overlaps with a public holiday. If unsure, check with your local planning authority.

Statutory Determination Period & the Decision

Once an application has been accepted as ‘valid’, the statutory determination period begins. For householders and minor developments, decisions should be made within 8 weeks. Major applications usually take longer, with a 13-week target unless significant environmental impacts are involved. If needed, the local planning authority may agree to extend the deadline with the applicant.

Applications determined by planning committee may take longer. Committees meet only once or twice a month and can only review a small number of applications per meeting.

What happens after a decision is made?

All decisions on applications will be published on the local planning authority’s website on the application page. This is known as the decision notice.

An application is either approved or refused. The case officer usually explains the decision in an ‘Officers Report’. If the Planning Committee disagrees with the officer’s recommendation, they may need to provide reasons separately.

Approved applications often include ‘planning conditions’. Major developments may also require a legal agreement with the local authority to secure financial contributions or public benefits. This is sometimes called a ‘Section 106’ agreement. Once signed, it is published online with the decision. Signing may take several months after approval is recommended. For further information about S106 and planning conditions, visit the Planning Practice Guidance pages, Planning Obligations and Use of Planning Conditions.

If refused, applicants can appeal within six months of the decision date shown on the notice.

The public cannot appeal a granted application. Their only option is a judicial review in the Courts. This is limited to legal grounds, not disagreements over facts or the development’s impact.

If you would like further information on how to challenge a proposal that has gained or is likely to gain planning permission please refer to our ‘How to Challenge Bad Development in Court’ guide here: Judicial review and planning decisions.

Find out more

You can read or print the full version of this guide by downloading the PDF here, which also contains part 2: how to get involved in planning: CPRE’s key steps. If you want to read a shorter version of part 2, view the web version here.