Exploring the seashore: a spotter’s guide

Over the past few years many of us have rediscovered and appreciated the delights of a visit to the British seaside more than ever.

Once we’ve had that bracing swim or our fill of fish and chips or ice cream, who can resist heading over to the rockpools or rummaging along the shore in search of wonderful wildlife?

If you’re lucky enough to be able to head for the beach, get your eyes peeled: here are some things to look out for.

Crusty crustaceans

Finding a crab is often the number one mission of any rockpooling child – and even quite a few adults! You might come across many different species but the most abundant is the common shore crab, also known as the green crab.

As well as scuttling about in rockpools, they can be found under stones, amongst seaweed or even burrowing in soft sand or mud where they scavenge on pretty much anything they can find. It’s tempting to try to pick up a crab, but please remember that they don’t like to be away from water or damp, cool places for too long.

To avoid being nipped, the best way to hold a crab is to grasp it on either side of its carapace (that tough upper shell). If you do pluck up the courage to pick one up, have a look on the underside and take a look at its tail, tucked under its body.

The shape of the tail will tell you if it’s a female (with a broad, oval tail) or male (with a narrow and triangular tail). Like shrimps and lobsters, crabs are crustaceans – animals with a hard shell that live in water.

In order to grow, they actually shed this outer shell occasionally – and in between moulting one shell and a new one hardening, they will have a ‘soft back’ – something else to be aware if you attempt to handle a crab! If its back does feel soft, immediately return it to its hiding place.

Snail super-grazers

Complaining about your beach picnic being spoiled by unpredictable weather? Spare a thought for marine creatures! Life between the tides is stressful for them because for half of each day they’re happily submerged in the sea, but they spend the other half exposed to the air with baking sun, freezing rain or drying winds to contend with.

Surviving all of this does have benefits, however. High sunlight levels and plenty of nutrients in the water are ideal growing conditions for seaweeds, microscopic algae (which might be what coats those rocks beneath your toes and makes them slippery) and tiny plant plankton. These offer rich pickings for animals to graze on.

Some of the most successful seashore grazers are marine snails such as winkles and topshells, and one of the most versatile of all, the limpet.

With their conical shell and slimy muscular foot, limpets can stick to the rocks, as the famous saying goes, ‘like a limpet’!, so that they don’t get ripped off by waves or hungry birds, crabs or fish. Clamping down also reduces their chance of drying out at low tide.

If you touch a limpet, you might feel it grip even tighter so that it’s almost impossible to remove. But please don’t try to yank a limpet off the rocks! Let’s leave these hangers-on in place. Pulling them can damage their shell edge, and when put back it won’t be able to seal down properly and will lose water and die.

And when everyone’s gone home, it’s limpet dinner time. They move around at high tide or at night, crawling over the rocks scraping off the thin film of algae using a specially adapted tongue. If you look carefully you can see their grazing tracks, looking a bit like miniature tyre tracks!

Rockpool menaces

Many seashore creatures will seek refuge in rockpools when the tide goes down to avoid being left high and dry on the exposed rocks. But these seemingly safe retreats hold their own dangers.

On a hot summer day, water can evaporate from pools making the water even saltier. This can then draw water out of the tissues of rockpool inhabitants. On a rainy day, the opposite happens and the saltiness can drop. If there’s a lot of life in a pool, then as things breathe they use up the oxygen and release carbon dioxide which can make the water more acidic.

And if all this wasn’t enough, predators also lurk in the pools ready to feast on a captive audience!

Rockpool fish such as blennies and gobies are often well camouflaged and will sit silently waiting to pounce on small shrimps or smaller snails – crushing through their shells with surprisingly sharp teeth. Sometimes blennies- which can grow up to 20 centimetres- can survive outside of rock pools under piles of moist seaweed or in damp holes of crevices.

So next time that you peer into a crack in the rocks you may see a pair of beady eyes staring out at you..!

One of the most unusual rockpool predators is the anemone. Some species, such as the beadlet anemone, can live out of water and look like squidgy red blobs on the rocks with a slimy and jelly-like feel.

But underwater, they come into their own and a ring of tentacles unfurls. Like their relatives the jellyfish, they’re armed with thousands of stinging cells which are triggered by passing prey such as small fish. These fire off harpoon-like barbs which paralyse their victims before they are drawn down into their mouths.

Most anemone stings are not powerful enough to harm humans, but to be on the safe side it is best not to poke them. And after all, none of us would much like to be prodded by inquisitive fingers!

Shout out for seaweeds

Although we get most excited by crabs, snails and anemones, it’s worth also spending some time marvelling at the plant life on the shore.

Just like green plants on land, the seaweeds and their floating microscopic cousins, plant plankton, are the basis of food chains. And seaweeds do an identical job to the plants on land: taking up carbon dioxide, releasing oxygen and making food. It’s been estimated that half of the oxygen that we breathe comes from ocean plant plankton!

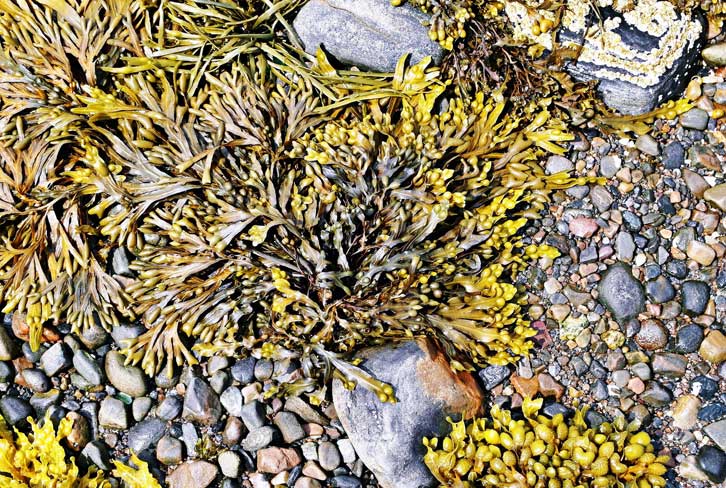

On the seashore, aside from those slippery microscopic algae covering the rocks, there are three groups of larger seaweed. The most obvious are the brown seaweeds and especially the ‘wracks’, which often can get washed up along the strandline after stormy weather.

Many of us adults will remember playing with bladderwrack, with its air-filled ‘bladders’ which can be popped a bit like bubble wrap! These are important to the seaweed, as they allow them to float up to get nearer to the sunlight.

Much more delicate than the wracks are tinier green and red seaweeds, often found creating beautiful underwater ‘gardens’ in rockpools. Some of these are even edible – but don’t eat them without finding out more first and checking the water quality of the beach. Most need to be ‘prepared’ in some way to make them more digestible.

Some are also surprisingly tasty! A small red seaweed called dulse tastes like fresh cucumber, and its relative the pepper dulse has a very strong peppery or garlicky taste.

Another, called sea laver, is dark brown in colour and looks like a thin film of polythene draped over rocks. This was actually a staple part of the diet of prehistoric coastal communities, and in many Celtic nations is still considered a delicacy and is eaten in the form of ‘laverbread’. It goes well with fried egg and bacon!

Following the Seashore Code

Finally, if you are able to get down to the beach and explore please remember to respect this amazing environment.

It’s best of all to just watch creatures where they are, but if you do pick them up, be sure to put them back gently and exactly where you found them, and turn stones back the same way. If you’re collecting creatures in a bucket, don’t keep them out of the water or away from their habitats for too long.

Many people will buy nets to go rockpooling. These are often not a very successful way of catching things and when you drag them along the sides and bottom of rockpools you can often cause a lot of damage, so their use is now being discouraged … and of course, they’re often made of plastic and are used once or twice and then break and are discarded.

Which of course brings us to one of the biggest things you can do when you go to the coast – please, please, please take all your litter home. You may even want to go one step further and take part in a beach clean, either as a group or as individuals or families.

You can find out more about plastic pollution, beach cleans and local campaign groups through organisations like the Marine Conservation Society and Surfers Against Sewage.

Dr Mark Ward is Somerset Wildlife Trust’s Brilliant Coast Project Manager. You can learn more about the great stuff being done by the Wildlife Trust and their Brilliant Coast project on their website. We love their work!