Harvest traditions in England

As summer draws to a close and the fields are cleared of crops, we turn our thoughts to the many ways that harvest season is marked across the country.

We take a look at some of the unusual ways that the change in seasons and the bringing in of the harvest (from the Anglo-Saxon word for autumn, ‘haerfest’) are celebrated in England.

Customs of the cornfield

Many harvest customs are connected with bringing in corn or other cereal crops. For example, ‘Hollaing Largesse’ is one of the traditions of the field. If a stranger passed a field in East Anglia where people were harvesting, the reapers would form a circle and shout ‘Holla Lar! Holla Lar! Holla Lar-Jess!’ The stranger would then be expected to make a donation to them to help pay for their harvest supper!

The last sheaf of corn had a particular significance in the field. In Cornwall, one of the reapers cuts this with a scythe and holds it aloft, shouting ‘I have ‘un! I have ‘un! I have ‘un!’ The other farmworkers reply ‘what ‘ave ‘ee? What ‘ave ‘ee? What ‘ave ‘ee?’

The reply is ‘A neck! A neck! A neck!’ Then everyone joins in shouting ‘Hurrah! Hurrah for the neck!’ In some other parts of the country, this differs slightly with the ceremony being called ‘Crying the Mare’.

That final handful of corn stalks might then have been woven into a ‘corn dolly’. This represented the spirit of the corn and was kept until the following spring to ensure a good harvest next year. In Hampshire, this is a Kern Baby and in Devon a Kirn Babby.

But the corn dolly isn’t always in the shape of a figure. A variety of regional dollies include the Cambridgeshire Handbell, Durham Chandelier and Worcester Crown.

In Carshalton, Surrey, there’s a ‘Straw Jack’. This is a large figure made from the last straw harvested from the fields, paraded through the streets and ceremoniously burned among music and general revelry.

Orchards and vines

Harvest time involves a whole array of other crops too, including apples, cherries, hops and potatoes. For families living in polluted parts of London in the early half of the 20th century, an annual September trip to the hop fields of Kent provided a breath of fresh air.

This was hardly Butlins; these were working holidays, and accommodation was cramped and unhygienic.

But for many children, it was a rare chance to see the countryside, encountering their first cows and running free around the woods and fields.

Apples are picked a little later in the year, usually in October. Over 2,500 varieties of these popular fruits were developed in the UK but nowadays it’s hard to find more than a couple of types in supermarkets that have been grown here.

That’s why it’s always a treat to go to an apple day or festival in the countryside where you can try a whole array of appetising apples!

Suppers and services

Naturally, a celebration of the harvesting of food often involves special feasts or dishes. Bread is often featured. A loaf might be baked into the shape of a wheatsheaf, and on Lammas Day, the first of August, bread baked with freshly picked corn was taken into the local church to be blessed.

Harvest suppers, or sometimes churn suppers, named after the big jug of cream that might be offered, were traditionally hosted by the farmer.

They brought together the community of people who’d helped bring in the crops as a way of saying thank you and celebrating a successful growing year.

It’s said that Reverend Robert Hawker, a vicar in Cornwall, introduced the idea of having a harvest festival in church in the 1800s, with hymns giving thanks for the bounty of the fields and orchards.

St Michael’s Mass, or Michaelmas, commemorates Archangel Michael who defeated Satan in the war of Heaven in the Bible. It’s celebrated on 29 September each year, and it was customary to eat a roast goose, fattened on the stubble of the harvest field, to mark the occasion.

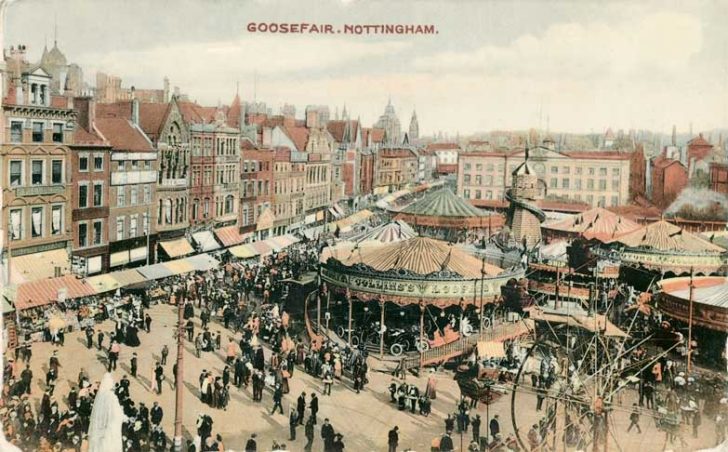

Goose Fairs were held across the country, including a famous one in Nottingham. Thousands of geese were walked to the city from Lincoln, Cambridge and Norfolk, to be sold.

Today Nottingham’s Goose Fair is over 700 years old, and times have changed. There are rollercoasters, big wheels, waltzers and dodgems – but you’re unlikely to see a goose!

If you’d like to find out more about English harvest traditions, we recommend checking out our friends at The Museum of English Rural Life (MERL).