Here be dragons!

St George’s Day marks the perfect time to celebrate the legends of England’s dragons! Landscapes associated with these fantastic beasts abound in every region – here we delve into the stories of five of our favourites…

Oxfordshire

Dragon Hill, formerly part of Berkshire, is mythologised as the site where George slew the dragon before it could devour the King’s daughter. The beast’s spilt blood seared the grass, leaving a bare patch of chalk on the hilltop that remains to this day.

The site lies along the ancient Ridgeway route, just below the Uffington White Horse – said to be the oldest chalk-cut hill figure in Britain at around 3,000 years old. With the Iron Age hillfort of Uffington Castle also nearby, the area provides a feast of history for dragon hunters.

Devon

The Exe Valley is said to be the haunt of a fire-breathing dragon protecting the treasures it buried underneath the two Iron Age hillforts of Dolbury Hill, Killerton and Cadbury Castle near Bickleigh (not to be confused with Somerset’s Cadbury Castle). Constantly swooping across the valley between the two sites, legend has it that the dragon escaped a slaying by never dwelling long at either location.

Dolbury Hill is actually an extinct volcano whose lava rock has been put to use in buildings around the National Trust’s Front Park estate at Killerton. A beautiful depiction of the estate’s Danes Wood, by five-year old Florence Farnell, was a deserving winner in CPRE Devon’s 2019 art competition for children.

Tyne and Wear

According to north east folklore, a young John Lambton once fished an eel out of the River Wear. It grew into a gigantic dragon – the Lambton Worm – while he was away on the 14th century Crusades. The monster began terrorising the family estate around Lambton Castle, before winding itself around what became known as Worm Hill near Washington.

Upon his return, John fought the dragon wearing armour covered in spear tips, which cut it to pieces (swept away by the river) as it tried to crush him. As well as its colourful mythology, the area is an important part of the Sunderland Green Belt, promoted by CPRE Durham volunteers as vital to the wellbeing of local people.

Somerset

A much less violent dragon slayer was St Carantoc, a holy man who is said to have helped King Arthur tackle a beast who was besieging Dunster. Carantoc simply draped his vestments around the dragon’s neck and prayed calmly, before leading it back into the marshes of the Somerset Levels where it lived in peace from then on.

South Yorkshire

Another imaginative resolution came when the knight, More of More Hall, saw off the dragon of Wantley with a carefully aimed kick to its only weak spot: its backside. More was even said to have commissioned some pointed Sheffield steel boots specially for the task!

The bawdy tale has been passed down us thanks to a comic ballad of 1685 that was popularised by inclusion in Thomas Percy’s 1767 Reliques of Ancient English Poetry. The ballad tells how the dragon would fly across the Don Valley from its den in Wharncliffe Crags to drink from Allman Well above Deepcar – a landscape later described by Sir Walter Scott in Ivanhoe as ‘that pleasant district of Merry England … haunted of yore [by] the fabulous Dragon of Wantley.’

More recently, CPRE South Yorkshire’s Green Belt Blueprint report has called for the valley to be protected from unsustainable development, and the river enhanced as a green link for people and nature.

Just ten miles from Wantley lies a plot of land at Totley purchased by John Ruskin in 1875 to be the base of his Guild of St George – a social and environmental movement inspired by his lifelong fascination with dragons and chivalry. For Ruskin, the dragon represented the damage and injustice created by industrialisation, which his Guild would challenge by providing places where urban workers could grow food and appreciate the countryside.

Ruskin’s original vision for the Guild shows what an influence it was on the formation of the ‘Council for the Preservation of Rural England’ fifty years later: ‘St George’s arrangements are to take the hills and streams and fields that God has made for us – to keep them lovely, pure and orderly as we can’.

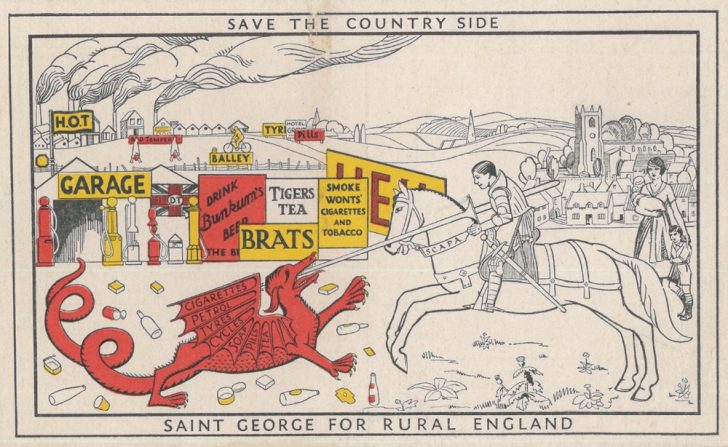

The Guild’s emblem, designed by Ruskin based on Carpaccio’s 1502 painting of St George slaying the dragon, was even borrowed for CPRE’s Save the Countryside campaign of 1928. In this postcard, St George represents CPRE’s fledgling movement for the defence of the countryside from a dragon symbolising commercial greed – also represented here in the form of speculative development, intrusive advertising and wasteful litter.

It’s clear that the mythology of England’s dragons will continue to endure in our imaginations and resonate with the issues of the day. As for the incredible locations that bring these stories to life, we salute the work of the organisations, volunteers and landowners who help to maintain and promote this rich landscape heritage.

With so many sites to explore, now is the perfect time to plan your next dragon hunting adventure!

A version of this article was originally published in CPRE’s award-winning magazine, Countryside Voices. You’ll have Countryside Voices sent to your door three times a year, as well as access to other benefits including discounts on attraction visits and countryside kit from major high street stores, when you join as a CPRE member. Join us now.