Leading the way: CPRE’s pioneering women

To mark International Women’s Day, we celebrate the achievements of the historic CPRE campaigners who shaped the way we think about the countryside and the wider environment.

Molly Trevelyan

A co-founder of CPRE, Molly was awarded an MBE in 1963 in recognition of over half a century of voluntary work for the countryside and her village of Cambo in Northumberland. She had been an advocate of women’s suffrage from 1904, and an early committee member of the National Federation of Women’s Institutes.

During 1926, Molly played a leading role in devising CPRE founding aims and objectives. She managed our fundraising and communications for nearly a decade on the principle that ‘to be effective, the preservation movement must interest a far greater circle of people’.

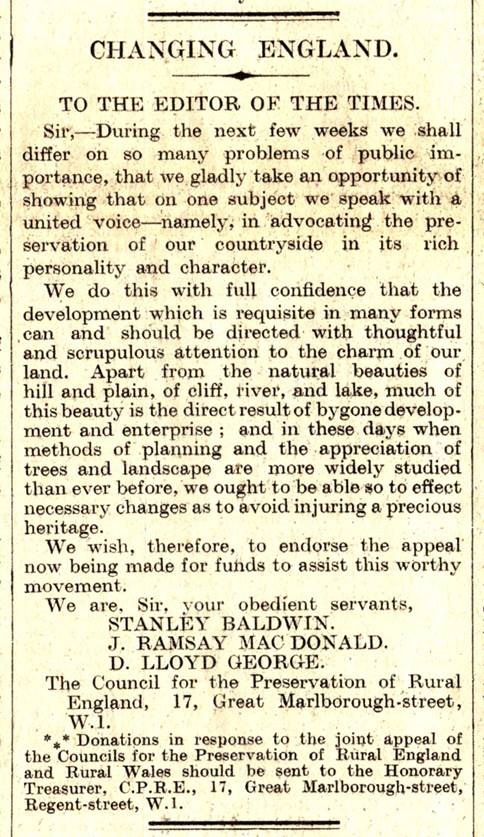

Her achievements in that field included securing a number of BBC radio appeals and extensive national press coverage. This included a letter to The Times in support of CPRE’s aims signed by party leaders (Baldwin, MacDonald and Lloyd George) during the 1929 General Election.

Molly’s commitment to education lead to the creation of special CPRE posters and pamphlets for schools, Scouts and Guides. Indeed, she remained a lifelong campaigner for schools to incorporate rural matters into the curriculum. She wanted all children to grow up with an appreciation of, and sense of responsibility for, the countryside.

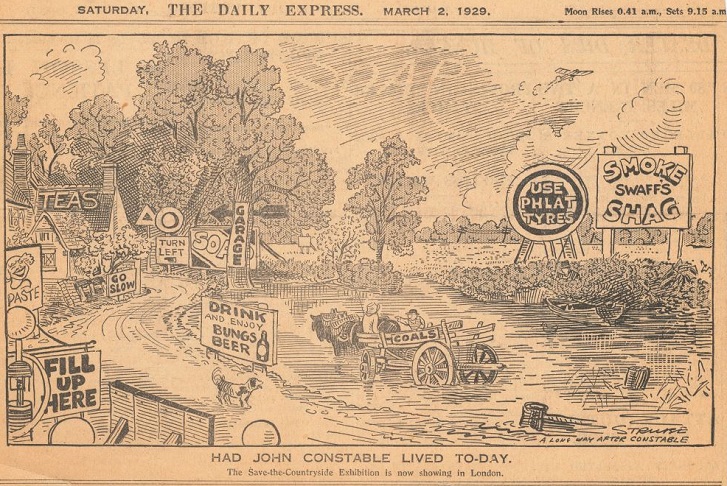

Being equally keen to influence political opinion, Molly devised the Save the Countryside travelling exhibition, which contrasted examples of damaging development with positive solutions.

Westminster Hall was one of over a hundred venues visited by the exhibition between 1928 and 1930. It was praised by MPs for highlighting the ‘lack of forethought in the development of the countryside’.

Responsible for recruiting CPRE’s network of public speakers, Molly enlisted the Essex conservationist Violet Christy to give the first speech promoting the new organisation. It took place at the Pioneer Club, an institution founded by the suffragist Emily Masingberd to engage women in progressive politics and social campaigning. A childhood friend of the crime-writer Dorothy L Sayers, Violet went on to give dozens of illustrated talks around the country on the work of CPRE. She later became a renowned local heritage expert and scout leader.

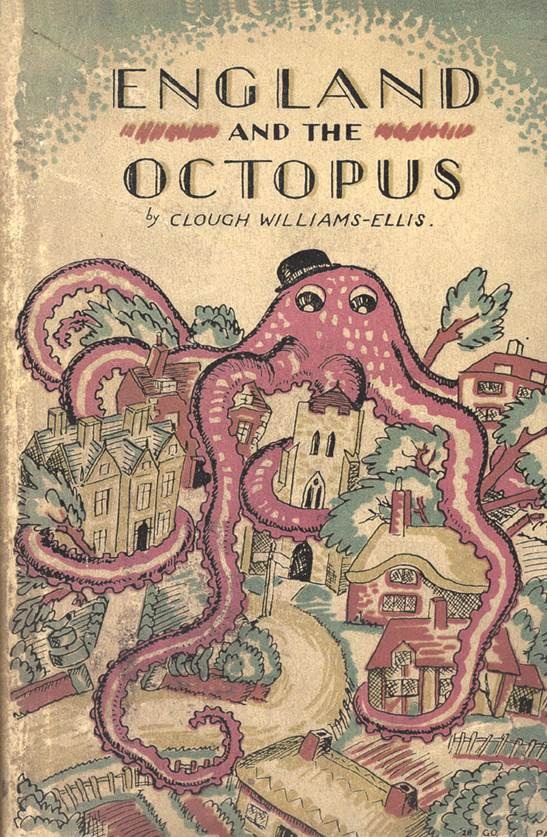

Another on Molly’s roster of speakers was the architect Clough Williams-Ellis. In need of a provocative polemic to send to schools, she commissioned his classic 1928 book, England and the Octopus – a rallying cry against urban sprawl that was a major influence on writers like Evelyn Waugh, DH Lawrence and George Orwell, and helped CPRE win a major victory with the Restriction of Ribbon Development Act in 1935.

Peggy Pollard

Someone else who’d been inspired by England and the Octopus was Peggy Pollard, who under the pseudonym ‘Bill Stickers’, had been part of the notorious ‘Ferguson’s Gang’ – masked preservationists who made anonymous donations to the National Trust in the mid 1930’s and considered themselves disciples of Clough Williams-Ellis.

As Honorary Secretary of CPRE Cornwall from 1936-46, Peggy’s pioneering work on coastal conservation informed a CPRE report of 1936 report, The English Coast: It’s Development and Preservation (featuring a chapter on the Northumberland coast by Molly Trevelyan), which recommended ‘the reservation all around the coast of a belt of open space, free from building’.

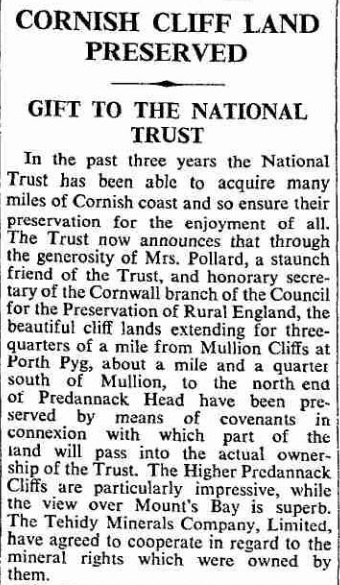

By 1937, The Times reported Peggy’s work to secure the purchase, for the National Trust, of ‘the beautiful cliff lands extending for three-quarters of a mile from Mullion Cliffs – a region where the Trust has hitherto had no foothold.’

Her efforts with CPRE helped ensure her beloved Cornish coast was designated as a protected Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty in 1959, and prompted a 1961 government request that local authorities should survey their threatened coasts – leading to the National Trust’s Enterprise Neptune initiative which has secured over 700 miles of coastline to date.

Ethel Haythornthwaite

Another legendary campaigner with a passion for landscape was Ethel Haythornthwaite, who through her efforts in Sheffield and the Peak District arguably did more for the cause of National Parks and Green Belts than any other individual.

Ethel set up the group that became CPRE Peak District and South Yorkshire in 1924 – two years before CPRE was created. In 1927, Ethel’s passionate appeal to the public helped raise the funds to purchase for the National Trust the 747-acre Longshaw Estate – threatened with development at the time – which became a key part of the Peak District National Park (England’s first) in 1951.

In 1932, Ethel’s skilful negotiation helped acquire another 448 acres of threatened land at Blacka Moor, which would soon become part of a Sheffield Green Belt in 1938 (again, England’s first).

When CPRE’s national director, Herbert Griffin, was called up by the army during the Second World War, Ethel spent much of 1942 as CPRE’s leader in the crucial debates on the planning and protection of the post-war countryside, becoming the only woman on the government’s National Parks Committee in 1945.

Her efforts saw her awarded the MBE in 1947 and were a huge factor in the creation of 1949’s National Parks and Access to the Countryside Act and a national system of Green Belts in 1955.

In 1945, looking back on her formative years, Ethel summed up the importance of access to the countryside for our health and wellbeing:

‘My childhood impressions of the city were a gloomy, noisy, shapeless phenomenon. But outside the city – there one began to live. The escape into clean air, the gradual return to nature – with this came satisfaction, peace, freedom, solitude, excitement.

‘One grew to become conscious of its profounder value, something beyond health and high spirits – something to worship’.

Ethel Bright Ashford

The war had seen another pioneering Ethel make a major impact for CPRE. In 1944, Ethel Bright Ashford – one of England’s first group of women barristers in 1922 – began CPRE’s campaign against air pollution, calling for measures that would eventually become the basis of the Clean Air Act 1956.

She led a CPRE deputation to the Minister of Health, recommending the ‘utilisation of our diminishing fuel resources with the greatest economy’ and strict enforcement of penalties for polluters.

Ethel’s legal expertise had already been vitally important in securing the protection of the green space on edge of towns and cities, rightly predicting – at CPRE’s 1937 national conference – that ‘the preservation of commons is a very important step towards green belts.’

She had also played a leading role in CPRE’s early campaign against litter, co-writing the influential 1933 report on ‘Rural refuse and its disposal’, possibly the first study into the impact of disposable packaging on the environment and health.

In his foreword, the minister of health Sir Hilton Young praised the study for highlighting ‘the valuable work that has been done by bodies such as the Women’s Institutes, in organising voluntary schemes for dealing with refuse and in stimulating the local authorities.’

He also commended the report’s promotion of ideas, such as the collection and re-use of bottles and jars, that would help with both the control of dangerous litter and the ‘valuable reclamation of land’ currently used for dumping waste.

Barbara Maude

The 1970s saw CPRE’s Barbara Maude take up the mantle on the environmental impact of litter and waste, arguing – in her 1975 book, The Turning Tide – that re-use and recycling must end the ‘throw-away’ culture.

Explaining the message of the book in The Times the following year, Barbara argued that the ‘the assumptions of perpetual surplus which have ruled for the past 150 years and which have led to the “consuming” or “wasting” society, are no longer valid. Our native ingenuity and initiative must be freed if we are to make the best of our resources.’

A beekeeper and environmental journalist, Barbara led on CPRE’s work for the European Conservation Year of 1970. She unveiled CPRE’s first hedgerow campaign at our national conference of 1969, calling for a halt to their destruction for ecological reasons – pointing to the effects on ‘many species of birds, animals, insects, wildflowers, and plants’.

As chair of CPRE Oxfordshire, Barbara was a formidable guardian of the county’s built and natural heritage – including the historic Beckley Park on Otmoor, which she helped save from a reservoir (campaigning alongside the writer Iris Murdoch), and later, a proposed route for the M40.

CPRE’s first anti-roads campaigner, Barbara opposed new motorways on environmental and economic grounds, helping to establish the right to challenge the need for motorways at public inquiries from 1973. The previous year has seen her establish a Transport Reform Group, led by local CPRE representatives, which aimed to press for less damaging modes of transport systems and innovation in ‘new forms of public transport and traffic management.’

Her foresight on the environmental impact of road-building continues to inform CPRE’s campaigning and was evident in a 1973 letter to The Times:

‘We should expect to economize, and apply the principles of thrift and conservation, in our use of what are non-renewable energy resources. Motorways are the most extravagant users of land and minerals – themselves finite and rapidly dwindling resources; and they encourage the continued extravagant use of fuel oils in transport.’