Wild enthusiasm: the ancestral tales of our landscapes

It was October and my partner and I were pitching our tent beside Loch Tay in Scotland. Wind howled, rain cascaded, clouds heaved and we were not having fun.

Our dog, Bryn, a Border collie, was watching from a distance and, despite my desire to be inside and dry, I could still see the humour of it. He seemed to ask: ‘Why can’t you just curl up under one of those boulders? Why are you so burdened?’ I envied him.

In the Old English epic Beowulf, the monster Grendel paces the mist-banded marsh. He, like Bryn, is part of the wilderness, whereas the hall he finds in the marshes, Heorot, is our tent: an aberration.

It is easy to imagine Grendel treading like a curious beast out of the mist towards the lamplit building. He can hear warriors feasting, singing and laughing inside and can detect their bond of community. He envies them. Unable to join them, he bursts into the hall and destroys them. Like so many monsters, he is portrayed as being outside human control; an enemy to civilisation.

The Sweet Track

Earlier this year I visited Somerset’s Avalon Marshes, where remnants of numerous prehistoric tracks weave through the wetland. One of these paths, the so-called Sweet Track, was made in the early Neolithic period out of X-shaped pairs of timbers driven into the ground, with planks fixed to the upper V to form bridges over the water. Walking a reconstruction of this path, I felt a bit like Grendel’s tame antithesis. From my designated route through the treacherous bog, I watched the convivial starling murmurations wheel over the marsh, and I wanted to be let in. But it was not my element. For all my yearning, I needed paths and, in time, I would need shelter. Whether we like it or not, we humans have long had to build to survive.

In so doing, it’s easy to forget about the wilderness, and even destroy it. We have destroyed so much already that we could easily condemn ourselves as monsters. Perhaps we are, but apathy and despair are not catalysts for the kind of judicious, imaginative, everyday action we must take for the natural world – not purely for the sake of wildlife or the countryside, but for ourselves, as an integral part of that world.

Old ideas of wilderness

Stories are also a kind of path into the wilds. In the Old English poem ‘Wulf and Eadwacer’, the female narrator describes a tumult of emotions regarding one she calls Wulf. In medievalist George Younge’s translation, the narrator bemoans: ‘Wulf is on one island, I’m on another/His isle’s remote, ringed by black fens.’

In this poem we travel into the wild as an expression of her emotion. In writing about this, alongside many other works from early medieval Britain that shed light on old ideas of wilderness, I have come to believe that we are not so burdened. To gain access to wild places by what we have created, or dreamed of, is to throw off coats, boots and rucksacks; to realise we are inseparable from them after all. It is there before language, before thought: our profound affinity with the wild.

About the author

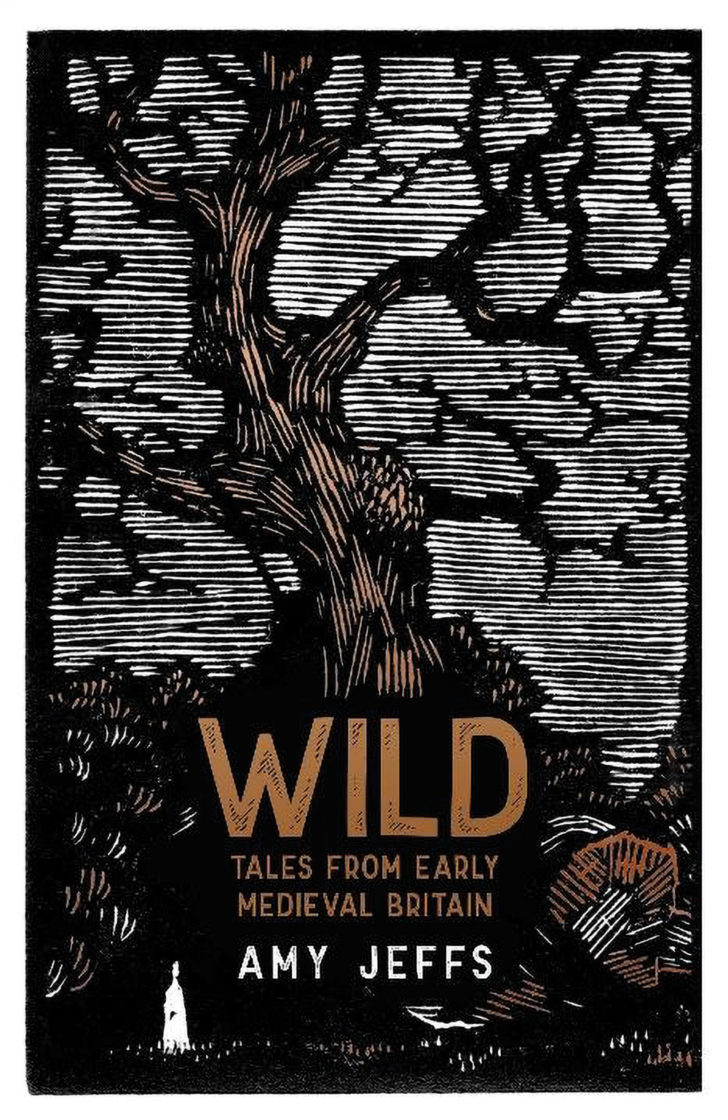

Amy Jeffs is the author of Wild: Tales from Early Medieval Britain.

A version of this article was originally published in CPRE’s award-winning magazine, Countryside Voices. You’ll have Countryside Voices sent to your door three times a year, as well as access to other benefits including discounts on attraction visits and countryside kit from major high street stores when you join as a CPRE member. Join us now.