To everything a season – autumn reflections

Autumn means the end of the year for some and a new term and start to an annual cycle for others. And maybe both at different times of life. Charles Moseley, in some extracts from his memoir of living in the Fens, reflects on both.

Autumn is the beginning

Years ago, I took on a very large allotment on the edge of the village to help make ends meet, for my job (then in publishing) paid little. It was on a bit of good land, where the high land, as we flatteringly call it, slopes down into the levelness of the Fen. It was separated from the Fen by a droveway and a stream – actually, a catchwater drain, dug in the 1600s to stop the little brooks of the spring line going into the fen….

We grew, my son and I, a small cash crop – wheat, or beet, or barley – and all our own vegetables. Sometimes too many: half a furlong of onions takes some hoeing and there were lots to give away instead of flowers or wine to people who invited us to dinner. (One year the swedes were the embarrassment.)

At this time of year, September, there would still be golden days of sun warm enough for me to work there with my shirt off, lifting the maincrop spuds, letting the bits of soil clinging to them dry off while I carried on lifting, and then bagging them for taking home. The onions – and I was always able to grow very good onions, for that land suited them – had been pulled some time back and had been drying off until their stalks were dry, but still flexible. Their shiny gold globes were warm with the sun, and their rustling outer skins, India paper thin, would come off and blow about in any breeze as I plaited the dry stems into long strings. I used to hang them on nails under the eaves of the woodshed where they would catch the sun and air.

Soon enough, the drones would be kicked out of my beehives by the busy little ladies getting ready for winter, and their deep-pitched hum would surround the hanging onions where many of them, for some unaccountable reason, always wanted to try to hibernate. Which they cannot do: this is the end of the road, chum: summer’s lease does have an end. Coming back along the drove, I used to notice that the trees looked tired, the leaves dull and somewhat ragged after months of weather and photosynthesising. The evenings draw in, and even after a day when I had given my land its first rough digging in the sweat of my brow, I needed to put on a shirt, a sweater, as I walked home. Days grow short and the wind gets a chill when you reach September.

It was – is – easy to see the year as coming to an end, the cycle once more complete, and to indulge in a sort of gentle melancholy. Yet autumn is really a beginning. It is much more than the elegiac fall of the leaf that has reminded so many poets of our own mortality. For in actual fact the year starts here, with getting ready: there is no spring without the dying of the old year into the beginning of new life.

Rhythms of field and wood

Older ages may have marked the turning of the year at the solstice when the sunset begins its northward journey, but you planned the work for your year, bound by the rhythms of field and wood and seedtime and harvest, from the time the swallows left – somewhere between the nights when the Perseid and then the Leonid meteor showers streak the night sky. And when great Orion begins to hunt the Hare across the early night sky you knew that it was high time to kill off and cure your pigs, fat with gorging on the beechmast and acorns of the woodlands and the fallen apples of orchards, and cure them down for the winter. For there would not be much fodder for them after this.

Archbishop Ussher of Armagh in the 1650s, following and developing (with great learning and serious calendrical maths) the Rabbinical tradition, calculated everything started in autumn: the world was created at nightfall on Sunday 22 October 4004 BC. His contemporary Dr John Lightfoot, ViceChancellor of the University of Cambridge, suggested 9am the next morning as the exact moment. And indeed October has advantages for a beginning, for then the food supply is plentiful and the apples are ripe.

The acorn’s journey

There is an old country saying, ‘The thorn is nurse to the oak.’ For years it never made sense to me, but by a serendipitous chain of unconnected conversations and reading, it does now. A mature oak produces many, many acorns, and not a one of them has a chance of growing beneath the deep shadow of the parent tree.

In season I pick up pockets full of them from the tree I planted decades ago by the river, and I scatter them in places where they might have a chance, where agricultural machinery can’t reach and where they will be out of the range of weedkillers. With one exception, that is the last I see of them, but I keep trying. However, the glamorous jay who visits my garden on his raids – actually there may be more than one, but I can’t recognise individuals – is the real hero of this story. For the jay in autumn will pick up to nine acorns in its beak or in its gullet and fly off to a bramble thicket or a hedge bottom, often enough hawthorn or blackthorn, where it buries them one by one. In early spring the acorn sprouts, and puts down a strong taproot, while at the same time opening two fleshy eaves full of protein to photosynthesise.

Now our clever Jay – I am inclined to give him/her a capital – remembers where he put the acorns a few months back, and does the rounds, and finds succulent protein-rich leaves pushing up to the sun through the leaf litter below the thorns. Just what a hungry bird needs at this thin time of year, and the infant oak with its long taproot can do without the leaves, for there are more where they came from. And so began many of the oaks that once clothed the wildwood country when men were few, and later made our houses, and were shaped into our ships, and so journeyed to the uttermost parts of the earth.

The coming of autumn

It is time. First hint of a change was a thickening of the light, a loss of sharp contrast, and a veil of high cloud approaching from over Ely way. Then little erratic flaws of wind began to gather the leaves that had fallen in the lee of walls and tree trunks, and outside our back door where the wild plum still held a few of its sour fruit. Little swirls of leaves rose and fell back. Then the flaws became a breeze, noticeably cool, that settled in the north east – the coldest quarter for this house, for on that side I planted no windbreak years back because it would have killed our view. Down the lane, which funnelled the wind, a wind more confident was soon dragging its feet in the accumulating dead leaves, as I loved to do when a child: who had been told not to.

The strengthening wind soon began to break the last hold the leaves had on the branches, and the note of its roar changed as the trees became naked. The drooping golden branches of the weeping willow by the river were soon flying out almost horizontal. The river’s tent was broken. A plastic bucket clattered off the garden table. The yew down the garden sang its gale song, a steady note, about A. On the river’s surface a miniature swell was developing, lines regularly following each other as if on a miniature ocean as the energy of the wind met the resilient friction of the surface. Jackdaws tumbled home to their roosts. It would be a big wind, and the last of summer was over.

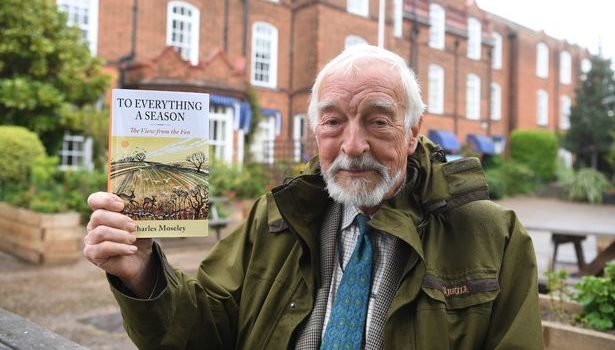

About the author

The above are extracts from Charles Moseley’s To Everything a Season: the View from the Fen published by Merlin Unwin Books. Charles is a long-time Fenland-dweller who teaches literature at Cambridge University when he is not writing books or tending his patch of the Fens.