Walking to untangle our minds

Walking the same route in Dorset every day for six months became an exercise in acute observation for Manni Coe and his brother, Reuben.

My brother Reuben was living in a home for adults with learning disabilities. After a breakdown and a period of isolation during the pandemic, he fell into a depression and became non-verbal, locked away from me and the rest of the world. Finding ways to help him unlock himself from what the doctors called a regression was not easy. He was disengaged, and I searched desperately for ways to reconnect him to his former self.

We were shielding together in a cottage near the Jurassic Coast in rural Dorset, and even though we were in the middle of a bleak winter, I tried to bring the outdoors in wherever possible. I bought flowers from the local supermarket. I lit scented candles. I watered the plants religiously. And every single day I took two walks: one alone, and one with Reubs, which would be more of a dawdle than a walk.

Being inactive for so long in the care home had left him with wasted muscles, and affected his balance. We took exactly the same route every day, and the familiarity helped Reuben regain his confidence. Every day he found it a little easier; getting up the first hill wouldn’t take him quite so long. He could feel the return of his own strength.

Cocooned by nature

Walking from the cottage, along the muddy lane flanked by thick hawthorn hedgerows on either side, we felt cocooned by nature. Rooks, gulls and ravens squabbled for airspace, and occasionally we could hear the far-off cry of a buzzard.

‘Like Ladyhawke,’ I would say, reminding Reuben of one of his favourite films. The light within his eyes seemed extinguished, but I fanned the embers of his memories constantly, hoping to reignite a flame.

‘Look, Reubs. There’s the tower of St Mary’s Church. We’re nearly there.’ He would adjust his rainbow beanie, take a deep breath, grab my arm and carry on. He was always willing to do so, however difficult he was finding it. That encouraged me and gave me hope; one step at a time. We followed the brook that meanders past the old mill houses of the sleepy village of Burton Bradstock, which wore winter like a bride’s veil.

Clipped hedges flanked residents’ gardens and although they were in their dormant state, the planting was neat and considered. Reuben identified his markers: the short-cut alleyway, the thatched cottage on the corner that reminded him of Tots TV (one of his favourite childhood programmes), and the post office. Each day he stopped to contemplate these monuments in his mind, proof of his progression.

On Fridays, we walked a little bit further to reach the sea. Reuben wanted me to pull him up and over the hill to reach the clifftops above Burton Bradstock beach, but I would gently encourage him to walk alone, however long it might take. We weren’t in a hurry. It seemed like the Earth had stopped spinning and we had all the time in the world.

Muddling through

There we would stand, hoods up against the blustery English Channel winds, gazing at a silvery horizon, splicing sea from sky like a knife edge. We would hug out there, for warmth and comfort, as I told him one day, ‘Well done, Booba. You made it! Now let’s go and enjoy our fish and chips.’

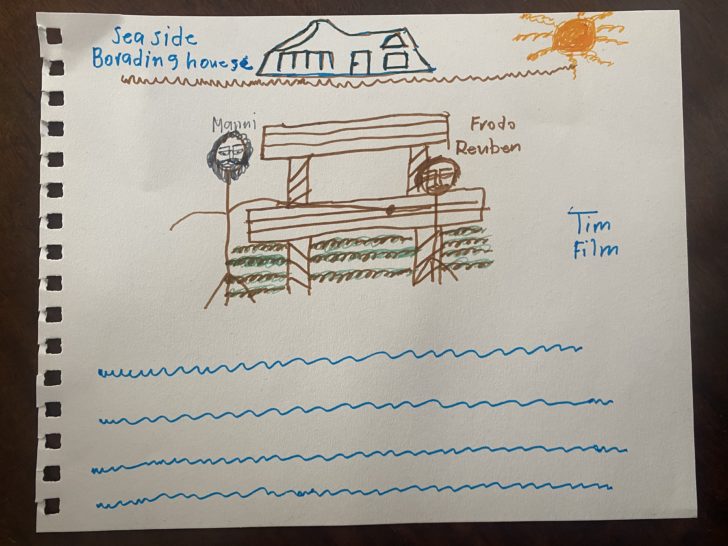

We bought our Friday takeaway from The Seaside Boarding House and sat on their arsenic-green picnic tables, backs to the wind. It was our special treat, a tradition that ended our week and started our weekend; a celebration of our brotherhood. Portland loomed low, dark and heavy to the east, and the gigantic cliffs of West Bay, slowly eroding into the sea, hung like cloaks on coat hooks to the west.

We were often alone out there, two brothers muddling through, staring at each other as we dipped our chips in tartare sauce, grateful for the world around us, grateful for each other. We would garner strength for our return walk, taking the same path homeward. Every single day I was amazed by how much more I noticed. Walking slowly afforded my mind the time to truly explore the landscape. As spring approached, new growth began to puncture the palette of winter, bringing with it a sense of renewal.

Little by little, the light returned to Reuben’s eyes. Little by little, his smile came back. Many weeks later, his voice began to return; a whisper at first, that grew a little stronger every day. Each time we reached the cottage after our walk to the sea, he would look at me and say, ‘I did it, brother. We’re home.’

Manni and Reuben

Manni and Reuben Coe are brothers whose memoir, brother. do. you. love. me. (Little Toller Books), is out now. Manni works as a walking guide in Spain and worldwide. Reuben, who has Down’s syndrome, loves drawing, and his art has been used by St Paul’s Cathedral. This month the brothers will appear at the Kendal Mountain Festival and Hay Festival Winter Weekend.