Hidden histories of the countryside: Black lives in south west England

From slavery to WW2 GIs, Louisa Adjoa Parker delves into the untold stories of the Black people who have left their mark on the English landscape.

The idea that black people only inhabit urban areas, and that the English countryside has always been white, is a myth. Yes, many black and brown people who came to the UK settled in our larger cities, but not exclusively – there are a multitude of rural histories which are yet to be heard.

The postcard image of the south west of England, with its rolling hills and coastline, evokes for some a nostalgic representation of Englishness, or rather, whiteness.

Yet, as I discovered years ago, black history is rich within the land of this place; in spite of commonly held misconceptions, the region has numerous connections with Africa, the Caribbean and Asia. As a black British woman of English and Ghanaian heritage who has lived in the south west for most of my life, I had no idea about this history – locally or nationally – until one afternoon at university, while studying racism and migration, I heard there was a grave in Devon of a black 18th-century person.

This knowledge sparked a curiosity in me, and since then I have carried out various research exploring the presence of BAME people in the south west.

Black doesn’t equal urban

This history is important – for people of colour who live in the region to see themselves reflected in local heritage; for the local white majority to understand that we belong, we are nothing new; and for those in urban spaces to understand that being black doesn’t equal urban. We have lived all over Britain for thousands of years. Local black history helps us all understand that as humans we are connected, and migration is not a contemporary phenomenon.

The West Country has been home to people of colour for centuries. They came as slaves or servants, sailors, teachers, writers, visiting royalty, boxers, students, and entertainers. The two world wars brought soldiers, prisoners-of-war and refugees.

Some of these people simply passed through, leaving traces of themselves behind (and in some cases, children). Others settled in the region. Numbers may be lower than in cities, but their stories matter: here are just a handful.

The legacy of slavery

Some, although not all, of the research undertaken in places such as Devon and Dorset explores links with transatlantic slavery.

Although we tend to think of Liverpool and Bristol when we think of slavery, British involvement has its roots in Devon – John Hawkins of Plymouth is recognised as the first English slave trader. Many south west ports were involved in slavery, as were many local families.

According to Lucy MacKeith, author of Local Black History: A beginning in Devon, ‘People at all levels of society were involved: sheep farmers, spinners and weavers who created cloth which was exported to Africa and the Americas, wool traders, bootmakers, food producers, metal workers who produced slave chains, shipbuilders … The list goes on.’

There are too many slave-owning families to list. Names include the Willetts of Dorset and St Kitts; the Halletts of East Devon and Barbados, the Swetes of Devon and Antigua; the Draxes of Dorset, Jamaica and Barbados, the Calcrafts, the Joliffes, the Pinneys of Dorset, Bristol and Nevis, the Daveys, and the Beckfords.

Plantation owners often brought enslaved people with them when they returned from overseas. In Devon, Lady Raleigh, wife of Sir Walter Raleigh, was one of the first people in England to have a young African ‘attendant’. My book Dorset’s Hidden Histories includes black people recorded in 18th and 19th century Dorset Parish Registers. Many were children, for example, ‘Henry Panzo, a Black Servant to Lieut. Brine R.N. aged 12 years, Poole, baptised 1817.’

When Richard Hallett returned from Barbados to Lyme Regis in 1699, he brought ‘a retinue of black servants’ with him. In 1702, Lyme Regis Town Court recorded that ‘a Black Negro servant of Mr Richard Hallett called Ando’ was accused of rioting in Broad Street. The way these people were treated would have varied according to the whims of their ‘owner’.

Some ‘servants’ were left money by their masters. For example, the will of Thomas Olive of Poole, 1753, includes the bequest of £900 to his ‘Negro woman’, Judith, and their daughters. Others were respected enough to have their own gravestone, such as the aforementioned eighteenth-century black servant at Werrington Church, on the border of Cornwall and Devon.

Philip Scipio was brought to England from St Helena by the Duke of Wharton. Scipio was buried in 1784, aged 18. He was described in the church register as ‘A black servant to Lady Lucy Morice.’ The bones of other black people must lie in unmarked (or as yet unrecorded) West Country graves.

After the slave trade was abolished in 1807, (with the help of abolitionists from the south west, such as Thomas Fowell Buxton) the government paid £20 million to British slave owners, who are listed in the Legacies of British slave-ownership database, as compensation for the loss of their ‘property’.

This wealth, along with the profits of slavery, helped build infrastructure, still visible today in the form of manor houses, estates, buildings and roads. Many sites are named after slave owners: the legacy of John Rolle, who owned plantations in the Bahamas, includes Bicton House (now Bicton College) and the Rolle Building at Plymouth University. Street names such as Drake, Hawkins and Raleigh also reflect this history.

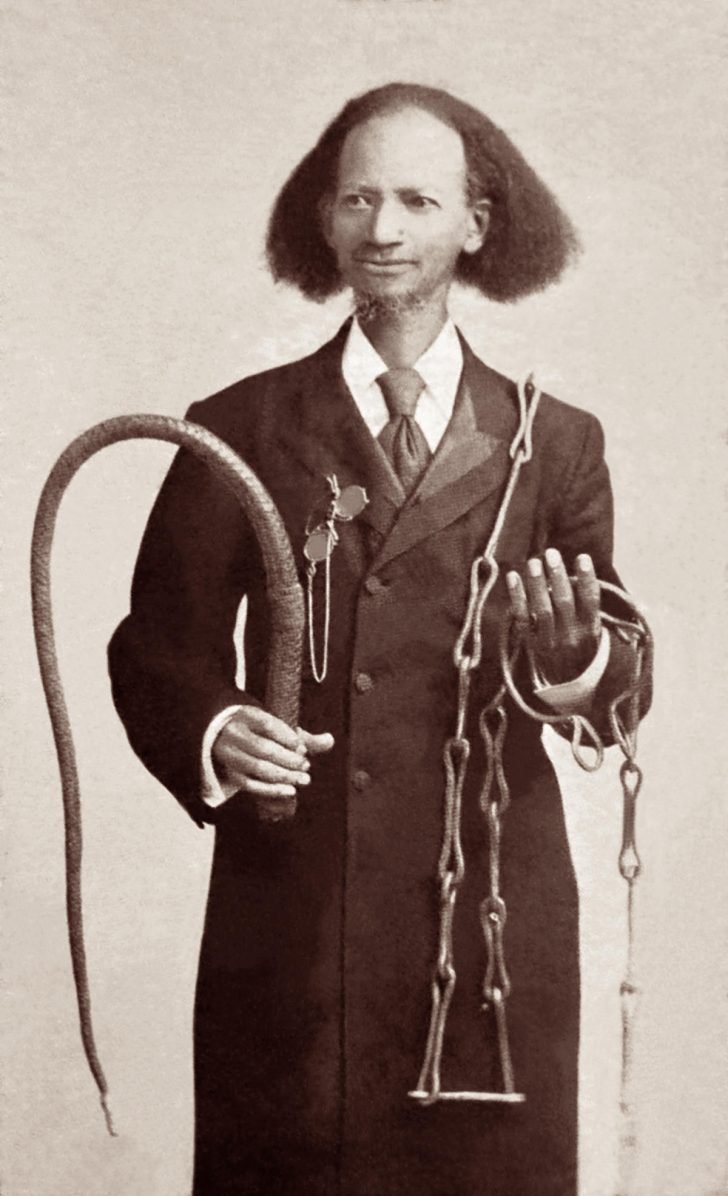

There’s much evidence of a continued black presence in the region post-slavery. Thomas Lewis Johnson settled in Bournemouth in the 1890s. Johnson was a missionary and former slave from Virginia, who spoke about Christianity and slavery and published a book called Twenty Eight years a slave.

Black entertainers performed in the region. Historian Jeffrey Green compiled a list of West Country Blacks in Victorian times, which includes Daniel Peter Hughes Taylor, son of a Freetown merchant, who attended Wesley College in Taunton, in 1869. His son was the composer Samuel Coleridge Taylor. Not everyone was successful – like their city counterparts, many black people in the area were plunged into poverty, and spent time in workhouses.

A wartime transformation

When World War II started, a whole new influx of people transformed the region as American soldiers came to the UK in the run-up to D-Day. Estimates of the numbers of African American soldiers, mostly GIs, range from 100,000 and 300,000, with many concentrated in port areas.

Although British authorities expressed concern about the arrival of so many black men (particularly with regards to them mixing with white women), British people generally welcomed them. It was ironic – the British didn’t like the segregation the US Army brought with it, yet Britain was still steeped in post-colonial racism.

While they didn’t object to a transient community, when it came to the offspring these men left behind it was a different matter.

The white Americans, often from the Southern states, were not prepared to see their black colleagues mixing with white women – a crime punishable by death under US law during wartime. Many fights occurred, and some black soldiers were killed. This didn’t stop the African Americans from mingling with locals, however, and many relationships were formed.

Across Britain a number of ‘Brown Babies’ (as the children of black GIs were known in the press) were left behind after the war. Carole Travers, who first shared her story for my book We Were Here: African American GIs in Dorset, was the result of a relationship between her white mother and a black soldier stationed in Poole.

Carole’s mother decided to keep her child, but was already married, to a Scot with pale skin and red hair. ‘I had black hair and dark skin,’ says Carole. ‘Something obviously wasn’t right.’

After decades of searching for her father, she recently discovered, through DNA testing, that he was Archie Elworth Burton, 1920-2004.

Not all the babies were able to stay with their mothers. Deborah Prior, who was born in 1945 to a widow from Somerset and a black American serviceman, spoke to Professor Lucy Bland on Woman’s Hour.

She spent five years at Holnicote House, a home for mixed-race children, after her mother was persuaded to give her up. This might seem remarkable in today’s Britain, where mixed-race people make up one of the fastest-growing demographic groups, but acceptance of relationships that cross communities has been a relatively recent occurrence meaning many people don’t know about their heritage.

These stories are a mere handful showing that black history in the UK doesn’t just have one narrative. Even just in south west England, it includes more than we would expect.

Learning about rural multi-ethnic history enables us to subvert ideas of a ‘golden age’ when Britain was an all-white nation. This has never existed, except in some people’s imaginations. British history – rural and urban – is intertwined with the history of non-white people. Black history is an integral part of British history.

There is already a plethora of information available, and yet more stories lie hidden in dusty records, waiting to be discovered.

Louisa Adjoa Parker is a poet, writer, and inclusion and diversity consultant who specialises in telling the stories of marginalised rural voices.

This article was previously published by Media Diversified and is reproduced here by kind permission.