Rural, affordable and sustainable

The crises in affordable housing, the cost of living and climate make the above combination more important than ever in new developments – as writer Catherine Early reports.

Developing new housing in rural areas can be a challenge in itself, and adding the extra elements of affordability and sustainability can result in an equation that few developers want to take on. Yet building in features such as lasting insulation, small-scale energy generation and a sustainable power source can make a huge difference to the cost of running a home – something which is ever more urgent now as energy prices surge.

However, according to Paul Miner, CPRE head of policy and planning, countryside communities are often left out in the cold when it comes to truly sustainable, high-quality, energy-efficient development. ‘We’ve long seen that rural households, which generally face higher-than-average heating bills, are too often overlooked in initiatives to reduce energy use,’ he says.

Previous research carried out by CPRE with Cambridge Architectural Research and Anglia Ruskin University in 2015 revealed that rural households receive only 1p for every pound spent by the government on energy efficiency, despite supporting nearly a fifth of England’s population.

Though new-build housing that is both affordable and built to high sustainability standards is rare in the countryside, there are developers and communities that have pulled it off. We spoke to some of those involved in – or living in – such schemes about their experiences.

Homes for local people

Nicola and Joe Davison and their nine-month-old daughter live in a flat in Burwash, East Sussex. Nicola grew up in the village, and her mum and grandmother both live there, next door to each other. But local rents – starting from £1,500 a month for a two-bed bungalow – almost forced them out of the village. ‘My mum is disabled and so is my nan, so we play a big part in helping them with their day-to-day life,’ says Nicola. ‘If we’d had to move any distance away, it would not only have made it difficult for us but also for them.’

Their home was built by the Hastoe Housing Association, which specialises in developing small-scale sites from four to 30 properties. These are often in designated landscapes such as National Parks or Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONBs), under the rural exceptions policy. Rural exception sites are those that would not normally be granted planning permission, such as on the edge of a village, lowering land costs. They come with the condition that only people with a local connection can live in them, and they can never be sold on the open market. The savings associated with the lower land costs can then be used to pay for sustainability features and materials.

Hastoe’s development director, Ulrike Maccariello, says that working closely with parish councils and designing homes that are in keeping with their surrounds are key to getting such schemes off the ground. On the sustainability front, the organisation’s strategy is to invest in the fabric of the building, since well-insulated homes need very little additional energy to keep warm. Although material costs can make this more expensive, it makes total sense for affordable housing, as Ulrike explains. ‘Building affordable housing is one thing, but you also need to keep living costs affordable. If people can’t afford to heat their homes, there can be issues with mould and condensation, and that leads to health problems,’ she says.

Green inside and out

The flat the Davison family lives in was built according to eco-friendly principles developed by the Passivhaus Institute in Germany. This method of building provides a continuous insulation seal around the core of a timber-framed structure, which keeps energy consumption to a minimum.

The majority of the flat’s heating comes from capturing the heat generated through the use of appliances for cooking, lighting and refrigeration. This captured heat is then used to warm incoming fresh air via a specially designed ventilation system. The flat also has a small combi boiler as a back-up.

Nicola has been living in the flat for nearly five years, and says the difference in running costs between her home and her mum’s – which uses storage heating – is ‘insane’. ‘It’s so much comfort to know I can be warm, and keep my baby warm, without having to sacrifice other things because of the price difference,’ she says.

The Davison home is so well insulated that even during the ‘Beast from the East’ cold snap in early 2018, they did not have to use the back-up heating. The cost savings on the heating mean that Nicola can afford to stay on maternity leave for longer. ‘That wouldn’t be an option if we were paying what some families of three are paying for their electricity,’ she notes.

Moving into the flat has ‘meant everything’, continues Nicola. ‘It meant that we can live in an area that I feel safe and comfortable in, where we could start a family, and where there are good schools. It’s just a relief that we get to stay near family, and in such a beautiful area where we’ve grown up.’

Social and sustainable rents

The village of Groton in Suffolk also suffered from a lack of affordable housing. Being on the edge of Constable country means that ‘every barn, chicken or cow shed’ has been converted into a house by people who live far away or who are retired, says councillor Bryn Hurren, of Babergh and Mid Suffolk District Councils, and young local people are totally frozen out. Social housing in the area has also been lost due to the right to buy, he adds.

Babergh and Mid Suffolk District Councils worked in partnership with Hastoe to build four new homes for local people in the village. Developed on former agricultural land, these include two one-bedroom bungalows and two two-bedroom houses, all for social rent for people with a local connection to Groton.

Work began on-site in February 2021, and the homes were completed nine months later. ‘The development took eight or nine years – it’s probably the longest one I’ve helped with,’ says Bryn. ‘But we got there, and the local people who have moved in are thrilled. Their families have written to thank us for sorting out their housing.’

Social housing keeps families together, Bryn says. People who are priced out of an area tend to be younger, and are more likely to have children, than those converting barns. As he sees it, it’s these young people and families that keep the community, and facilities such as local schools, going.

The Groton homes have ground-source heat pumps, which transfer heat from the ground outside to heat buildings, and are close to Passivhaus standard in their level of insulation. ‘I went to visit on a bitter spring day and they were warm inside, without any heating on,’ Bryn recalls. He believes energy-efficiency and clean energy features should be statutory on all homes. ‘It’s something to work towards,’ he says. ‘I would hope all housing associations would start to put these features in.’

‘Fabric first’ homes

When Warehorne Parish Council in Kent recognised the need for more affordable housing for local people, it contacted English Rural, a housing association that had built similar homes in the village 25 years ago. After major delays due to the financial crash, which made the land unviable to develop, the project was finally funded by the sale of a custom-built plot on the open market. The result was a development of two houses and two flats, completed in 2019.

The site, known as Goldfield, is another rural exception site, and will be owned and managed by English Rural. The housing association applied the principles of ‘fabric first’ construction, designing the homes to be very energy efficient. High levels of insulation have been used, along with air-source heat pumps to provide affordable heating and hot water for residents at low cost.

A family who moved into one of the houses had previously been living with one of the couple’s parents. ‘They had quite poor housing circumstances, but they’re delighted with their new home,’ says Alison Thompson, deputy development director at English Rural. ‘The lady is actually now a parish councillor. I think that’s exactly what local needs is – people who want to stay in the community want to put something back into it as well.’

Driving change

Like many coastal communities, the popular Dorset seaside town of Bridport suffers from a lack of affordable housing for local people, due to the proliferation of second homes and holiday homes. In 2008, a group of local people got together to act on this problem. They decided to develop a ‘co-housing’ project on the north-west edge of town, with 53 affordable homes for sale and rent, all of which would include energy-efficiency and nature-friendly features.

Now the housing project, named Hazelmead, is finally coming to fruition, with residents moving in one terrace at a time as builders finish the homes. The project experienced many challenges over the years, including delays caused by funders’ and planners’ lack of familiarity with co-housing models and objectives. ‘Co-housing is a way of living that gives people private space and shared facilities,’ explains Monica King, society secretary of Bridport Cohousing, a Community Land Trust. ‘That means people don’t need to own so much, so it’s greener and less expensive. And the big payoff is that you get society, if you want it.’

Developing co-housing requires extreme dedication, says Monica, who has been working on the project for 13 years. For such a project to be successful, it needs ‘someone who is devoted to it, and puts it before everything’.

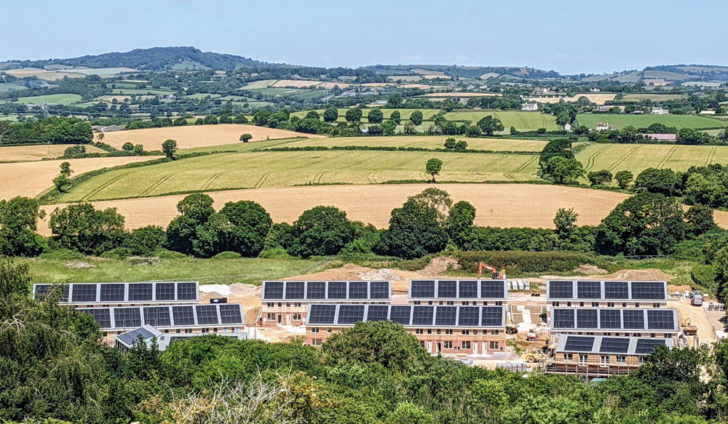

The homes are being built with near-Passivhaus levels of insulation, along with solar panels, air-source heat pumps, a large battery store and a site-wide micro grid, which will distribute the renewable solar energy generated around the development. Streets will be car-free, with households typically allowed one car each. A ‘Common House’ will provide a communal space for all to use, as well as practical facilities such as washing machines and tools for loan.

The homes are reserved for people with local connections only, and the development is managed by the community. ‘I think the main driver for the project is sustainability,’ says Monica. ‘One of the values that we all share is that we want to reduce our carbon footprint.’

CPRE’s view on greener homes

CPRE believes that sustainability standards for both new homes and the wider developments they sit in should be introduced urgently. Research in 2020 by CPRE and UCL found that 75% of all new housing estates built since 2005, when the government last audited design quality, were mediocre or poor against a range of quality criteria, including key sustainability provisions such as energy efficiency and public transport links.

The government’s new Future Homes Standard, due to come into force in 2025, will address energy efficiency, but we believe the measures should be introduced with greater urgency than the government has so far proposed. In particular, we believe that the government can and should aim for zero carbon in all new builds by no later than 2030, rather than just a 75-80% reduction by 2050, as is currently mooted.

Find out more about CPRE’s campaigning for better-quality homes at cpre.org.uk

About the author

Catherine Early is a freelance journalist specialising in the environment and sustainability.

A version of this article was originally published in CPRE’s award-winning magazine, Countryside Voices. You’ll have Countryside Voices sent to your door three times a year, as well as access to other benefits including discounts on attraction visits and countryside kit from major high street stores when you join as a CPRE member. Join us now.